Full speed ahead: how rapid CAR-T manufacturing can shape the cell therapy landscape

Cell & Gene Therapy Insights 2025; 11(4), 515–532

DOI: 10.18609/cgti.2025.062

Autologous CAR-T cell therapy has revolutionized treatment options and improved therapeutic outcomes for B cell leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma patients worldwide. However, patient access, cost and time to receive their personalized medicine remain a hurdle for many patients waiting to receive a cell therapy. Reducing CAR-T cell manufacturing time is one strategy to shorten the vein-to-vein time, bringing life-saving therapies to patients faster. Beyond expedited access to treatment, an accelerated manufacturing process may also enhance CAR-T cell durability, leading to improved clinical responses. This review highlights current advancements in the rapid cell therapy manufacturing space, while also discussing the challenges to widespread adoption of a rapid process including meeting required clinical doses, the need for development of expedited release assays and quality control procedures. Despite the challenges, adoption of a rapid process holds promise to increase manufacturing capacity and reduce costs to help further improve patient access.

Introduction

Almost a decade ago, the first CAR-T cell therapy was granted US FDA approval for the treatment of pediatric B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [1]First-ever CAR-T-cell therapy approved in US. Cancer Discov. 2017; 7(10), OF1–OF1.. Since then, immuno-oncology and more specifically, cell therapy has emerged as a leading modality in the treatment and eradication of various hematologic malignancies including several lymphoma subtypes and multiple myeloma. Autologous CAR-T cell therapies, to date, are the most developed of all genetically engineered lymphocyte therapies, with several others on the horizon. Today, there are a total of seven commercial CAR-T cell products that have made astonishing impacts on patients’ lives worldwide (Table 1) [2]Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018; 378(5), 439–448. [3]Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019; 380(1), 45–56. [4]Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR-T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017; 377(26), 2531–2544. [5]Locke FL, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel as second-line therapy for large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022; 386(7), 640–654. [6]Shah BD, Ghobadi A, Oluwole OO, et al. KTE-X19 for relapsed or refractory adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: Phase 2 results of the single-arm, open-label, multicentre ZUMA-3 study. Lancet 2021; 398(10299), 491–502. [7]Abramson JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. Lancet 2020; 396(10254), 839–852. [8]Munshi NC, Anderson Jr LD, Shah N, et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021; 384(8), 705–716. [9]San-Miguel J, Dhakal B, Yong K, et al. Cilta-cel or standard care in lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023; 389(4), 335–347. [10]Roddie C, Sandhu KS, Tholouli E, et al. Obecabtagene autoleucel in adults with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024; 391(23), 2219–2230.. However, the rise of CAR-T therapies has also presented new challenges, spanning from concerns for neurotoxicity and the onset of secondary T cell malignancies to scaling manufacturing and increasing the accessibility and affordability of these life-saving therapies [11]Posey AD Jr, Young RM, June CH. Future perspectives on engineered T cells for cancer. Trends Cancer 2024; 10(8), 687–695. [12]Elsallab M, Ellithi M, Lunning MA, et al.Second primary malignancies after commercial CAR-T-cell therapy: analysis of the FDA Adverse Events Reporting System. Blood 2024; 143(20), 2099–2105. [13]Khare S, Williamson S, O’Barr B, et al. Sociodemographic factors influencing access to chimeric antigen T-cell receptor therapy for patients with non-hodgkin lymphoma. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2025; 25(2), e120–e125. [14]Ghilardi G, Williamson S, Pajarillo R, et al. CAR-T-cell immunotherapy in minority patients with lymphoma. NEJM Evid. 2024; 3(4), EVIDoa2300213. [15]Hernandez I, Prasad V, Gellad WF. Total costs of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell immunotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2018; 4(7), 994–996. [16]Karschnia P, Miller KC, Yee AJ et al. Neurologic toxicities following adoptive immunotherapy with BCMA-directed CAR-T cells. Blood 2023; 142(14), 1243–1248..

| Table 1. Vein-to-vein time for commercial CAR-T cell therapies. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Product name | Commercial name | Indication | Vein-to-vein time |

Tisagenlecleucel | Kymriah® | FL, DLBCL, ALL | 3–4 weeks |

Axicabtagene ciloleucel | Yescarta® | FL, DLBCL | 3.5 weeks |

Brexucabtagene autocel | Tecartus® | MCL, ALL | 2–3 weeks |

Lisocabtagene maraleucel | Breyanzi® | FL, LBCL, MCL, CLL, SLL | 3–4 weeks |

Obecabtagene autoleucel | Aucatzyl® | ALL | 3 weeks |

Idecabtagene vicleucel | Abecma® | MM | 4 weeks |

Ciltacabtagene autoleucel | Carvykti® | MM | 4–5 weeks |

ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia. CLL: chronic lymphocytic leukemia. DLBCL: diffuse B cell lymphoma. FL: follicular lymphoma. LBCL: large B cell lymphoma. MCL: mantle cell lymphoma. MM: multiple myeloma. SLL: small lymphocytic lymphoma. | |||

The goal of this review is to shed light on potential solutions to some of the largest bottlenecks in CAR-T cell therapy–patient access and vein-to-vein (V2V) time. Currently, the time between patient apheresis and drug product (DP) infusion, which will be subsequently referred to as V2V time, can range from 3–5 weeks, with a median time of 31 days (Table 1) [17]Ehsan H, Ahmed F, Moyo TK, et al. Real-world analysis of barriers to timely administration of chimeric antigen receptor T-Cell (CART) therapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Blood 2023; 142(Suppl. 1), 7393–7393.. Despite improvements in process engineering designed to increase scalability of CAR-T manufacturing, including increased reliance on automation and construction of large capacity manufacturing suites, time to administration remains a significant barrier for many patients with aggressive disease. Eligible patients for CAR-T cell therapy are generally heavily pretreated and have exhausted at least 1–3 lines of prior therapy before meeting eligibility criteria for CAR-T cell therapy. Specifically, B cell lymphoma patients are at an increased risk of disease progression making faster access critical in these situations. Put into perspective, it is estimated that nearly 30% of patients who are initially prescribed a CAR-T therapy never undergo leukapheresis, and 20% of patients who do undergo leukapheresis do not proceed to infusion of the therapy [18]Sureda A, El Adam S, Yang S, et al. Logistical challenges of CAR-T-cell therapy in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a survey of healthcare professionals. Future Oncol. 2024; 20(36), 2855–2868.Sureda A, El Adam S, Yang S, et al. Logistical challenges of CAR-T-cell therapy in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a survey of healthcare professionals. Future Oncol. 2024; 20(36), 2855–2868.. Furthermore, rapid disease progression, clinical ineligibility and declining clinical status have been identified as the leading factors for patient drop-off [18]Sureda A, El Adam S, Yang S, et al. Logistical challenges of CAR-T-cell therapy in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a survey of healthcare professionals. Future Oncol. 2024; 20(36), 2855–2868.Sureda A, El Adam S, Yang S, et al. Logistical challenges of CAR-T-cell therapy in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a survey of healthcare professionals. Future Oncol. 2024; 20(36), 2855–2868.. In additional support of these findings, mathematical simulations have illustrated that the V2V time has significant implications on patient outcomes including mortality rates, and life expectancy post CAR-T cell infusion [19]Tully S, Feng Z, Grindod K, et al. Impact of increasing wait times on overall mortality of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in large B-cell lymphoma: a discrete event simulation model. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2019; 3, 1–9. [20]Vadgama S, Pasquini MC, Maziarz RT, et al. ‘Don’t keep me waiting’: estimating the impact of reduced vein-to-vein time on lifetime US 3L+ LBCL patient outcomes. Blood Adv. 2024; 8(13), 3519–3527..

The V2V time encompasses a wide range of activities including shipping and receiving of the apheresis starting material, manufacturing the drug product, release testing, and finally transportation to the infusion site. Clinical care considerations for the patient as well as clinician availability and scheduling also factor into the V2V time. This insight will focus exclusively on one aspect of the V2V time—the CAR-T cell manufacturing process; however, we acknowledge that reducing time to infusion will require a combined effort on multiple fronts. While the duration of the manufacturing process is only one determining factor of the V2V time, shortening this time will not only expedite time to patient infusion, but may also result in a more durable, higher quality drug product (DP) capable of inducing even deeper clinical remissions.

When considering all commercial autologous CAR-T cell products, conventional manufacturing processes can require 7–14 days of cell manipulation to generate the clinical dose and require many distinct process steps to produce the drug product [21]Tyagarajan S, Spencer T, Smith J. Optimizing CAR-T cell manufacturing processes during pivotal clinical trials. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020; 16, 136–144. [22]Pavlic J, Fury B, Mayo J, et al. Optimizing CAR-T cell therapy: reducing manufacturing time and examining T cell memory phenotypes in B cell lymphoma. Blood 2024; 144(Suppl. 1), 7254–7254.. Briefly, the autologous CAR-T process begins upon receipt of patient apheresis at the manufacturing site. Bulk apheresis is composed of a heterogeneous population of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), which may be further enriched for CD3+ T cells through a selection or sorting process. Alternatively, CD4+ and CD8+ cells may be isolated together or separately to achieve a desired CD4:CD8 ratio, requiring a more labor-intensive manufacturing process. Furthermore, there have been additional efforts to isolate specific T cell subsets to serve as the starting material in the manufacturing process. T cell differentiation status has been shown to correlate with anti-tumor efficacy and in vivo persistence which has inspired an effort to isolate naïve and memory T cell subsets defined by a panel of surface markers including CD62L, CCR7, CD127, CD45RA, and CD45RO [23]Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Torabi-Parizi P, et al. Central memory self/tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells confer superior antitumor immunity compared with effector memory T cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2005; 102(27), 9571–9576. [24]Gattinoni L, Klebanoff CA, Palmer DC, et al. Acquisition of full effector function in vitro paradoxically impairs the invivo antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2005; 115(6), 1616–1626. [25]Sommermeyer D, Hudecek M, Kosasih PL, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells derived from defined CD8+ and CD4+ subsets confer superior antitumor reactivity in vivo. Leukemia 2016; 30(2), 492–500..

Upon enrichment of the intended T cell population, the cells are typically stimulated through activating antibodies to the CD3ζ chain of the T cell receptor (TCR) as well as the co-stimulatory molecule, CD28 [26]Ayala Ceja M, Khericha M, Harris CM, et al. CAR-T cell manufacturing: major process parameters and next-generation strategies. J. Exp. Med. 2024; 221(2), e20230903.Ayala Ceja M, Khericha M, Harris CM, et al. CAR-T cell manufacturing: major process parameters and next-generation strategies. J. Exp. Med. 2024; 221(2), e20230903.. Additionally, cytokine signals such as IL-2, IL-7, and/or IL-15 are included to support T cell expansion and CAR-Transgene delivery and favor preservation of less differentiated cell populations [27]Alizadeh D, Wong RA, Yang X, et al. IL15 enhances CAR-T cell antitumor activity by reducing mTORC1 activity and preserving their stem cell memory phenotype. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019; 7(5), 759–772. [28]Cieri N, Camisa B, Cocchiarella F, et al.IL-7 and IL-15 instruct the generation of human memory stem T cells from naive precursors. Blood 2013; 121(4), 573–584. [29]Xu Y, Zhang M, Ramos CA, et al. Closely related T-memory stem cells correlate with in vivo expansion of CAR.CD19-T cells and are preserved by IL-7 and IL-15. Blood 2014; 123(24), 3750–3759.. Currently, all commercial CAR-T products rely on lenti- or retro-viral transduction to drive stable CAR-Transgene expression. Once genetically modified, CAR-T cells are permitted to expand in culture for several days to ensure the intended clinical dose is met. The expansion process is performed under culture conditions that are favorable to T cell cultivation which can assist in the elimination of contaminating cell populations and additional impurities such as residual lentiviral plasmid DNA. Finally, the cells are harvested and formulated at the intended dose in cryoprotectant to preserve cell viability during the freezing and thawing process [26]Ayala Ceja M, Khericha M, Harris CM, et al. CAR-T cell manufacturing: major process parameters and next-generation strategies. J. Exp. Med. 2024; 221(2), e20230903.Ayala Ceja M, Khericha M, Harris CM, et al. CAR-T cell manufacturing: major process parameters and next-generation strategies. J. Exp. Med. 2024; 221(2), e20230903.. This marks the conclusion of the manufacturing process, at which point the material is tested for release. CAR-T cells are evaluated for several safety, characteristic and functional critical quality attributes including purity, sterility, transgene copy number, viability, and potency. The final dose that will be administered to the patient is a reflection of the percentage of surface CAR expressing T cells as a proportion of total T cells present in the DP. Once the DP passes all release testing, it is shipped back to the infusion center and the patient is prepared for treatment, which commonly includes a lymphodepletion regimen to generate space for T cell engraftment.

The subsequent sections will delve deeper into each phase of the manufacturing process, highlighting differences between conventional and rapid manufacturing and the accompanying considerations surrounding the adoption and integration of a rapid process.

Current landscape of rapid manufacturing

Reducing the current autologous CAR-T manufacturing process from several days to 24–72 h is a paradigm shift when considering the widespread use of first-generation CAR-T cell manufacturing processes for several clinical and commercial CAR-T products (Table 2). Here, we will review various stages of the manufacturing process and how current efforts toward achieving a rapid process must address these critical process steps to generate a safe and efficacious DP.

| Manufacturing overview and development state of rapid (<72 h) and expedited (4–6 days) CAR-T programs. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Rapid CAR T (target) | Activation | Gene editing strategy | Manufacturing time | QC/release | Development stage |

GC012F (CD19/BCMA) FasTCAR Platform | CD3/CD28 | Lentivirus | 1 day | 8 days | Phase 1b |

BMS986354 (BCMA) NexT Platform | n.a. | Lentivirus | 5–6 days | n.a. | Phase 1 |

YTB323 (CD19) T-Charge Platform | CD3/CD28 | Lentivirus | <2 days | 6 days | Phase 2 |

Dash CAR T (CD19) | CD3/CD28 | Retrovirus | 2–3 days | n.a. | Preclinical |

KITE-753 (CD19/CD20) | n.a. | Lentivirus | 5 days | <9 days | Phase 1 |

PRGN-3007 (ROR1), PRGN-3005 (MUC16), PRGN-3006 (CD33), UltraCAR-T Platform | None | Electroporation | 1 day | n.a. | Phase 1 |

Ingenui-T (CD19) | n.a. | Lentivirus | <3 days | n.a. | Preclinical |

n.a.: not accessible. | |||||

Patient apheresis or starting material

Most pharmaceutical companies have adopted a centralized manufacturing design, wherein patient apheresis is shipped from a clinical collection site to a central manufacturing facility within a predetermined time window. To meet global patient demand, there may be several manufacturing sites distributed throughout North America, Europe, and Asia to support late-stage clinical and commercial manufacturing. If apheresis receipt cannot occur within the pre-determined time window due to transportation constraints, the apheresis may be cryopreserved prior to shipment to the manufacturing site to preserve cell quality (Figure 1). Given the uncertainties that may cause delays in shipment, cryopreserving apheresis near the collection site can be used to reduce the risk of manufacturing failures due to apheresis quality and simplifies manufacturing logistics. However, there is also a benefit to employing fresh apheresis, especially when considering moving toward a rapid process. The cryopreservation process imposes an extrinsic stress on PBMCs which can negatively impact the quality and viability of cells that are recovered after thaw [30]Hanley PJ. Fresh versus frozen: effects of cryopreservation on CAR-T cells. Mol. Ther. 2019; 27(7), 1213–1214.. These effects could be exacerbated when considering patient material that may be more fragile in nature. On average, the recovery rate for cryopreserved PBMCs is 80%, therefore utilizing fresh material will permit access to greater numbers of T cells, which could be critical in meeting clinical dose in the context of a shortened process [31]Brezinger-Dayan K, Itzhaki O, Melnichenko J, et al. Impact of cryopreservation on CAR-T production and clinical response. Front. Oncol. 2022; 12, 1024362.. Additionally, cryopreserved material is likely to experience greater cell death over the first 48 h of culture, which may significantly impact cell yield from a rapid process [32]Panch SR, Srivastava SK, Elavia N, et al. Effect of cryopreservation on autologous chimeric antigen receptor T cell characteristics. Mol. Ther. 2019; 27(7), 1275–1285.. However, the potential rewards of fresh apheresis are not without risk–pursuing a path to fresh material in a centralized manufacturing model will require extensive effort in the transport logistics to ensure that the material can be sent from the apheresis collection center to the manufacturing site on an expedited timeline (typically within 24–48 h) to maintain high cell viability and functionality. When considering the implementation of a rapid process, the starting material can have potentially large implications on critical quality attributes of the DP including cell viability. Fresh apheresis generally provides a benefit to T cell health due to the elimination of the cryopreservation process, which can help improve cell performance in the manufacturing process.

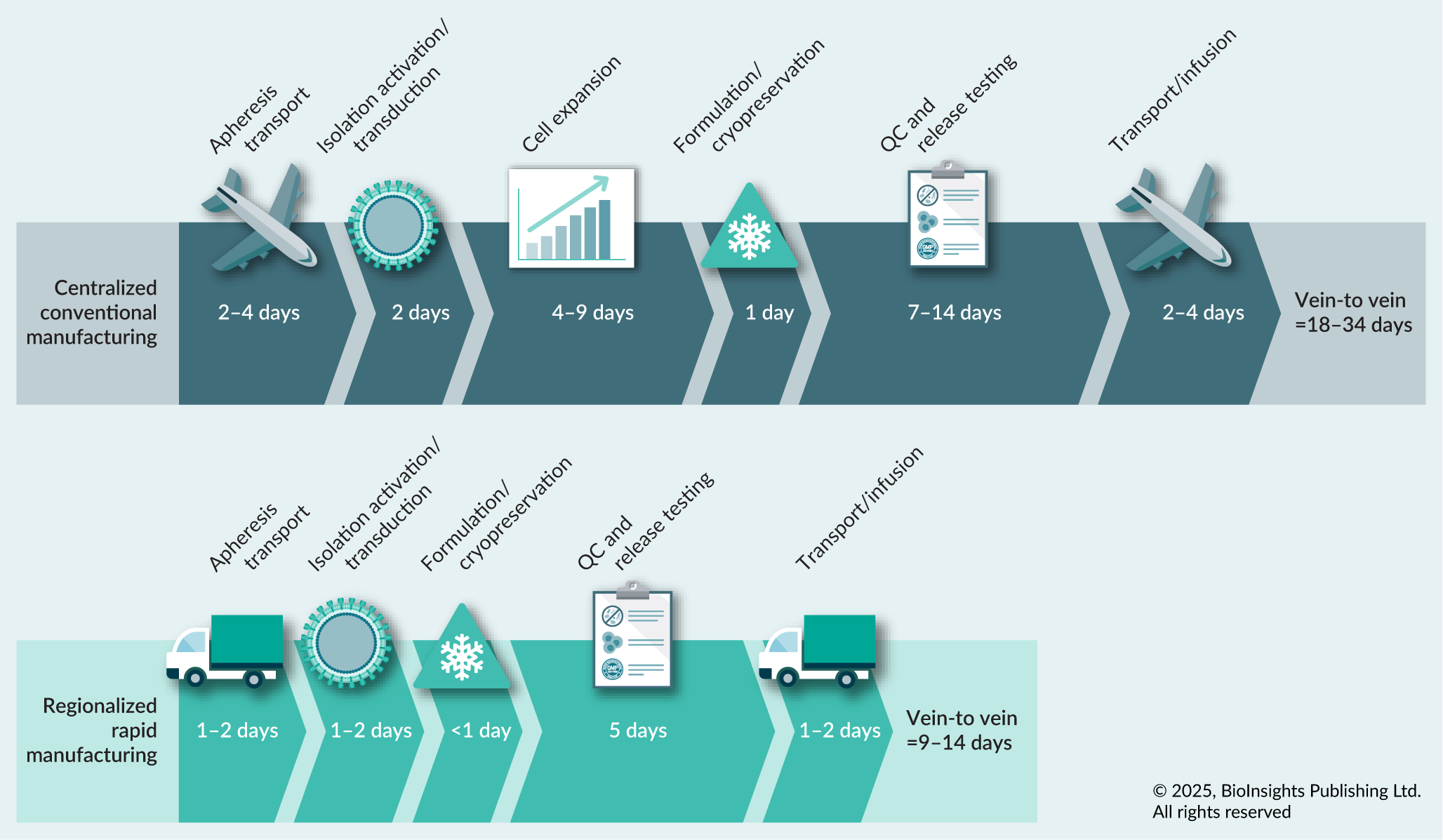

| Figure 1. Overview of process development stages and accompanying timeframes in conventional (top) and rapid (bottom) manufacturing settings. |

|---|

|

| © 2025, BioInsights Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved. |

T cell enrichment

CAR-T cell manufacturing begins upon receipt of the apheresis at the manufacturing site. Typically, the apheresis is washed prior to T cell enrichment or selection. Despite some conventional manufacturing processes beginning with unselected PBMCs, the shortened duration of a rapid process poses increased purity challenges of the resulting DP. The culture conditions and cytokine supplements used in conventional manufacturing processes favor the expansion of CD3+ T cells and ultimately deter the growth of contaminating tumor cells, lymphocyte, and monocyte populations. A shortened process increases the risk of infiltrating non-T cell types in the final DP and therefore an enrichment process is generally preferred to control for DP purity. Rapid processes are currently relying on either density gradient centrifugation approaches (Novartis’s T-Charge™ platform), CD4/CD8 positive selection microbeads, or CD3/CD28 Dynabeads™ (AstraZeneca/Gracell’s FasTCAR-T and Hrain Biotechnology’s Dash CAR-T platforms), which can both purify and activate T cells [33]Ikegawa S, Sperling AS, Ansuinelli M, et al. T-Charge™ manufacturing of the anti-BCMA CAR-T, durcabtagene autoleucel (PHE885), promotes expansion and persistence of CAR-T cells with high TCR repertoire diversity. Blood 2023; 142(Suppl. 1), 3469–3469. [34]Dickinson MJ, Barba P, Jager U, et al. A novel autologous CAR-T therapy, YTB323, with preserved T-cell stemness shows enhanced CAR-T-cell efficacy in preclinical and early clinical development. Cancer Discov. 2023; 13(9), 1982–1997. [35]Yang J, He J, Zhang X, et al. Next-day manufacture of a novel anti-CD19 CAR-T therapy for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: first-in-human clinical study. Blood Cancer J. 2022; 12(7), 104. [36]Chen X, Ping Y, Li L, et al. CD19/BCMA dual-targeting Fastcar-T GC012F for patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an update. Blood 2023; 142(Suppl. 1), 6847–6847. [37]Ahmad S, Chan T, Sayed A, et al. 232 Non-viral engineered next generation CD19 UltraCAR-T with membrane bound IL-15 (mbIL15) and PD-1 blockade preserves stem cell memory/naïve phenotype and enhances anti-tumor efficacy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024; 12(Suppl. 2), A266–A266. [38]Liao JB, Stanton SE, Chakiath M, et al. Phase 1/1b study of PRGN-3005 autologous UltraCAR-T cells manufactured overnight for infusion next day to advanced stage platinum resistant ovarian cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023; 41(16 Suppl.), 5590–5590. [39]Wang H, Tsao ST, Xiong Q, et al. 621MO Preclinical study of DASH CAR-T cells manufactured in 48 hours. Ann. Oncol. 2022; 33, S828. [40]Deng T, Deng Y, Tsao ST, et al. Rapidly-manufactured CD276 CAR-T cells exhibit enhanced persistence and efficacy in pancreatic cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2024; 22(1), 633. [41]Ghassemi S, Durgin JS, Nunez-Cruz S, et al.Rapid manufacturing of non-activated potent CAR-T cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022; 6(2), 118–128. [42]Anaya D, Kwong B, Park S, et al. Development of Ingenui-T, a rapid autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T manufacturing solution using whole blood, for treatment of autoimmune disease. Cytotherapy 2024; 26(6 Suppl.), S9. [43]Costa LJ, Kumar SK, Atrash S, et al. Results from the first Phase 1 clinical study of the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) Nex T chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy CC-98633/BMS-986354 in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). Blood 2022; 140(Suppl. 1), 1360–1362.. While the enrichment times are comparable across these platforms, the use of a multipurpose bead-bound activation reagent (i.e., CD3/CD28 Dynabeads) requires de-beading prior to DP formulation and can result in significant cell loss because of the affinity of the surface receptors to the crosslinking antibodies.

While some current commercial products may begin the manufacturing process with bulk apheresis or leukapheresis material, adoption of this trend in an abbreviated process raises concerns regarding purity of the DP. Therefore, the field has largely agreed that an enrichment step is necessary to remove any unwanted or contaminating cell populations prior to T cell activation and transduction.

T cell activation

Nearly all conventional CAR-T cell manufacturing processes require naïve T cell activation to facilitate viral transduction. The cell therapy field has largely conformed to activating T cells through the CD3/CD28 mediated pathway. The use of crosslinking antibodies to these receptors has been widely adopted in commercial manufacturing which simulates the interaction between a T cell and an antigen presenting cell (APC), and ultimately invites a T cell-mediated immune response accompanied by T cell differentiation and clonal expansion. The agonistic antibodies to CD3 and CD28 can be bead bound (Dynabeads), soluble or plate immobilized, or conjugated to polymeric nanomatrices (TransAct™). T cell activation triggers a series of transcriptional and metabolic changes within the cell, and ultimately induces expression of surface proteins that are critical to viral infection. Viral fusion to the cell membrane and subsequent endocytosis is dependent upon the binding of the viral glycoprotein G from the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV-G) to the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDL-R) on the T cell surface. It has been previously demonstrated that LDL-R expression is upregulated upon T cell activation, specifically peaking around 24 h post activation [44]Wang YI, Hao YN, Shen MY, et al. The expression of LDL-R in CD8+ T cells serves as an early assessment parameter for the production of TCR-T cells. In Vivo 2023; 37(6), 2480–2489. [45]Bonacina F, Moregola A, Svecla M, et al. The low-density lipoprotein receptor-mTORC1 axis coordinates CD8+ T cell activation. J. Cell Biol. 2022; 221(11).. These findings have provided justification for T cell activation prior to lentivirus introduction in virally engineered CAR-T cell therapies. Unsurprisingly, quiescent, non-dividing lymphocytes, such as naïve T cells, are historically less susceptible to viral infection. They have demonstrated accompanying low rates of reverse transcription of viral RNA and generally have reduced levels of transgene expression which poses a significant challenge when attempting to reach a specific clinical dose of CAR expressing cells [41]Ghassemi S, Durgin JS, Nunez-Cruz S, et al.Rapid manufacturing of non-activated potent CAR-T cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022; 6(2), 118–128..

However, recent findings in both preclinical and clinical stage research have demonstrated that potent CAR-T cells can be generated without an activation stimulus, enabling the retention of naïve or progenitor T cell subsets which demonstrate enhanced in vivo persistence and superior metabolic fitness [46]Corrado M, Pearce EL. Targeting memory T cell metabolism to improve immunity. J. Clin. Invest. 2022; 132(1), e148546. [47]Zheng W, O’Hear CE, Alli R, et al. PI3K orchestration of the in vivo persistence of chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells. Leukemia 2018; 32(5), 1157–1167.. Ghassemi et al. illustrated a lentiviral based approach to 24-h CAR-T generation without T cell activation [41]Ghassemi S, Durgin JS, Nunez-Cruz S, et al.Rapid manufacturing of non-activated potent CAR-T cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022; 6(2), 118–128.. Utilizing a multifaceted approach including the addition of cytokine signals, IL-7 and IL-15, deoxynucleosides, short periods of serum starvation, as well as re-design of the culture vessel to increase the colocalization of viral particles with T cells, the authors demonstrated that surface CAR protein could be detected as early as 12 h after lentivirus addition. Although the translation of this approach into clinical scale manufacturing has yet to be demonstrated, the potential therapeutic benefits of a naïve T cell-derived DP should inspire additional efforts in this space [48]Turtle CJ, Hanafi LA, Berger C, et al.CD19 CAR-T cells of defined CD4+:CD8+ composition in adult B cell ALL patients. J. Clin. Invest. 2016; 126(6), 2123–2138. [49]Fraietta JA, Lacey SF, Orlando EJ, et al. Determinants of response and resistance to CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat. Med. 2018; 24(5), 563–571. [50]Gattinoni L, Klebanoff CA, Restifo NP. Paths to stemness: building the ultimate antitumour T cell. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012; 12(10), 671–684. [51]Sabatino M, Hu J, Sommariva M, et al. Generation of clinical-grade CD19-specific CAR-modified CD8+ memory stem cells for the treatment of human B-cell malignancies. Blood 2016; 128(4), 519–528..

Similarly, Precigen, a clinical stage biopharmaceutical company, has developed an approach that does not utilize ex vivo activation. The UltraCAR-T® platform is an overnight manufacturing process that uses a semi-closed electroporation system, UltraPorator™, for gene transfer [52]Sallman DA, Elmariah H, Sweet K, et al. Phase 1/1b safety study of Prgn-3006 Ultracar-T in patients with relapsed or refractory CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia and higher risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2022; 140(Suppl. 1), 10313–10315. [53]Chan T, Scott SP, Du M, et al. Preclinical evaluation of Prgn-3007, a non-viral, multigenic, autologous ROR1 Ultracar-T® therapy with novel mechanism of intrinsic PD-1 blockade for treatment of hematological and solid cancers. Blood 2021; 138(Suppl. 1), 1694–1694.. Non-viral genetic engineering strategies are more susceptible to gene transfer without an activation signal than lentiviral based approaches, however, they can pose additional toxicity concerns, as later described.

While there are advantages to infusing a naïve T cell population including retention of a quiescent cell population, conventional manufacturing processes rely on the use of an activation stimuli to facilitate lentiviral integration and ultimately drive CAR expression which has resulted in potent, efficacious DP. When considering a rapid process, it is possible that alternative activation strategies may be preferred to facilitate earlier CAR-Transgene integration and reduce the impacts of activation induced cell death or terminal differentiation programs. Finally, it is well understood that T cell activation drives clonal expansion, which encompasses several days in a conventional manufacturing setting. However, in the context of a rapid manufacturing process, the cell product is harvested prior to the logarithmic expansion phase with the expectation that expansion will commence upon in vivo infusion. It remains unclear if in vivo expansion kinetics of unactivated and previously activated CAR-T cell products are comparable and may be an important area of investigation when developing a rapid process.

Vector delivery

As discussed previously, current clinical CAR-T cell therapies rely on viral vectors to deliver the CAR-Transgene and drive stable surface CAR expression. However, additional non-viral genetic engineering strategies are under development, some of which have been employed in rapid manufacturing settings (Table 2) [37]Ahmad S, Chan T, Sayed A, et al. 232 Non-viral engineered next generation CD19 UltraCAR-T with membrane bound IL-15 (mbIL15) and PD-1 blockade preserves stem cell memory/naïve phenotype and enhances anti-tumor efficacy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024; 12(Suppl. 2), A266–A266. [53]Chan T, Scott SP, Du M, et al. Preclinical evaluation of Prgn-3007, a non-viral, multigenic, autologous ROR1 Ultracar-T® therapy with novel mechanism of intrinsic PD-1 blockade for treatment of hematological and solid cancers. Blood 2021; 138(Suppl. 1), 1694–1694.. Briefly, non-viral gene editing and delivery strategies including transposons, designer nucleases, electroporation and nanoparticles have been reviewed in detail elsewhere [54]Atsavapranee ES, Billingsley MM, Mitchell MJ. Delivery technologies for T cell gene editing: Applications in cancer immunotherapy. EBioMedicine 2021; 67, 103354.. While many of these strategies are accompanied by their own unique sets of advantages, inefficient plasmid delivery, impacts to cell viability, safety concerns for off-target delivery and scalability remain significant hurdles that hinder adoption into clinical manufacturing.

Currently, the majority of rapid manufacturing efforts including those by Novartis (T-Charge), and AstraZeneca/Gracell (FasTCAR) (manufacturing time <72 h) as well as expedited manufacturing efforts by Kite (huCART19-IL-18) and Bristol Myers Squibb (NexT; manufacturing time 4–6 days), use viral-based delivery strategies (Table 2) [33]Ikegawa S, Sperling AS, Ansuinelli M, et al. T-Charge™ manufacturing of the anti-BCMA CAR-T, durcabtagene autoleucel (PHE885), promotes expansion and persistence of CAR-T cells with high TCR repertoire diversity. Blood 2023; 142(Suppl. 1), 3469–3469. [36]Chen X, Ping Y, Li L, et al. CD19/BCMA dual-targeting Fastcar-T GC012F for patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an update. Blood 2023; 142(Suppl. 1), 6847–6847. [40]Deng T, Deng Y, Tsao ST, et al. Rapidly-manufactured CD276 CAR-T cells exhibit enhanced persistence and efficacy in pancreatic cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2024; 22(1), 633. [42]Anaya D, Kwong B, Park S, et al. Development of Ingenui-T, a rapid autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T manufacturing solution using whole blood, for treatment of autoimmune disease. Cytotherapy 2024; 26(6 Suppl.), S9. [55]Svoboda J, Landsburg DJ, Nasta SD, et al. Safety and efficacy of armored huCART19-IL18 in patients with relapsed/refractory lymphomas that progressed after anti-CD19 CAR-T cells. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024; 42(16 Suppl.), 7004.. While the timing of the transduction can span from the time of activation to ~24 h post-activation, mechanistically much has to happen inside of the cell to achieve stable CAR surface expression. First, the viral envelope protein VSVG must bind to low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors on the T cell surface to enter the cell. Viral RNA must then be unpackaged, reverse transcribed and subsequently integrated into the host cell genome. Complete integration of the CAR encoding DNA and subsequent transcription, translation and trafficking to the cell surface can require 72–96 h. The desire to shorten the entire CAR-T manufacturing process to less than 72 h therein poses a challenge, since accurate detection of surface CAR protein through conventional flow cytometric approaches is required to formulate the final dose.

Although viral vectors are the most established of the genetic engineering strategies, there are additional challenges that could impede their widespread use in rapid processes. Rapid processes employing ‘no-expansion’ protocols need to begin with cell numbers that far exceed the number of cells needed to meet the clinical dose. Not only must the DP bag be produced, but material needed for release testing, regulatory retains and potentially a back-up DP dose must also be generated while accounting for some cell loss during the harvest process. Given that there will likely be cell loss within the first 24 h due to activation-induced cell death or transduction-related toxicity, this could mean starting the process with greater than 1 × 109 CD3+ T cells. Depending on the multiplicity of infection (MOI) used to transduce the material, this places a substantially increased demand on viral vector supply and will subsequently increase the cost of raw materials required to generate DP. As previously indicated, the cost of cell therapies is one aspect with direct implications on patient access. Therefore, it may be worthwhile to allocate resources for the exploration of more economical strategies of gene transfer.

Aside from the use of lenti- or retro-virus, electroporation of T cells with the Sleeping Beauty transposon system to simultaneously drive expression of an anti-MUC16 CAR and safety kill switch in a 1-day manufacturing process is currently being investigated in a Phase 1/1b trial for recurrent platinum resistant ovarian cancer (Table 2) [38]Liao JB, Stanton SE, Chakiath M, et al. Phase 1/1b study of PRGN-3005 autologous UltraCAR-T cells manufactured overnight for infusion next day to advanced stage platinum resistant ovarian cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023; 41(16 Suppl.), 5590–5590. [53]Chan T, Scott SP, Du M, et al. Preclinical evaluation of Prgn-3007, a non-viral, multigenic, autologous ROR1 Ultracar-T® therapy with novel mechanism of intrinsic PD-1 blockade for treatment of hematological and solid cancers. Blood 2021; 138(Suppl. 1), 1694–1694.. This process is achieved using Precigen’s proprietary UltraPorator electroporation system and is capable of meeting large scale manufacturing requirements as evidenced by the infusion of clinical doses over 300 × 106 UltraCAR-T cells. This platform has demonstrated, preliminarily, that electroporation can be implemented into an expedited process while circumventing the risk of impurities associated with viral transduction. However, it should be noted that while this process removes the bottleneck associated with generating large volumes of high titer viral material, electroporation of purified T cells at this scale (starting material >1 × 109 cells to generate a clinical dose of 300 × 106) will require large amounts of GMP grade plasmids which can be a significant expense in raw materials. Additionally, there are ongoing safety concerns from regulatory agencies surrounding the use of transposons in CAR-T manufacturing due to the concern for potential off-target integration, insertional mutagenesis and oncogenic risk to the patient requiring close long-term monitoring of adverse events in the treated population [56]US FDA. Considerations for the Development of Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cell Products: Guidance for Industry. 2024..

The use of both viral and non-viral approaches in rapid CAR-T cell manufacturing have been employed, however both strategies are subject to high raw material costs required to generate clinical doses upwards of 100 × 106 CAR+ cells. Looking forward to the technological advancements in CAR design including advanced armoring strategies and secretion of tumor microenvironment (TME) modulating agents, it is possible that future generations of CAR-T cell products may demonstrate clinical efficacy at reduced clinical doses which would make a rapid process more achievable from a process and manufacturing capacity perspective [57]Uslu U, June CH. Beyond the blood: expanding CAR-T cell therapy to solid tumors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024; 43(4), 506–515..

Elimination of expansion phase

The end-to-end time for many of the rapid processes in development and under clinical investigation are within 72 h. This process duration aligns with the lag observed in T cell expansion kinetics after activation. Prior to clonal expansion, T cells must undergo several cellular processes including upregulation of specific genes, expansion in cell size and entrance into an active cell cycle from a quiescent state. The lag in T cell proliferation can span from 24–72 h and therefore minimal cell expansion happens in the context of a rapid protocol (Figure 1).

Without a period of T cell expansion, one of the greatest challenges for process development is the ability to meet the clinical dose. However, current data indicate that non-expanded cells have a superior phenotype and higher in vivo proliferative capacity, therefore it is possible that an effective dose may be significantly lower than conventional T cell therapies. Consider an example in B cell lymphoma—in the standard manufacturing Phase 1 trials, a dose range of 25–200 × 106 was evaluated. In the rapid manufacturing trials for YTB323, which expresses the same validated CD19-targeting CAR as tisgenlecleucel, and huCART19-IL-18 the dose ranges were significantly lower ranging from 3–70 × 106 cells per patient [34]Dickinson MJ, Barba P, Jager U, et al. A novel autologous CAR-T therapy, YTB323, with preserved T-cell stemness shows enhanced CAR-T-cell efficacy in preclinical and early clinical development. Cancer Discov. 2023; 13(9), 1982–1997. [55]Svoboda J, Landsburg DJ, Nasta SD, et al. Safety and efficacy of armored huCART19-IL18 in patients with relapsed/refractory lymphomas that progressed after anti-CD19 CAR-T cells. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024; 42(16 Suppl.), 7004.. It is encouraging that the overall response rates (ORR) and complete response rates (CRR) were comparable across both manufacturing platforms [34]Dickinson MJ, Barba P, Jager U, et al. A novel autologous CAR-T therapy, YTB323, with preserved T-cell stemness shows enhanced CAR-T-cell efficacy in preclinical and early clinical development. Cancer Discov. 2023; 13(9), 1982–1997. [55]Svoboda J, Landsburg DJ, Nasta SD, et al. Safety and efficacy of armored huCART19-IL18 in patients with relapsed/refractory lymphomas that progressed after anti-CD19 CAR-T cells. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024; 42(16 Suppl.), 7004.. On the other hand, when considering the multiple myeloma indication where doses in the rapid process were decreased ~90% from 100–300 × 106 to only 10–20 × 106, the CRR achieved by infusion with the rapidly manufactured DP was 60% lower than those observed in the CARTITUDE-1 and IMMagine-1 trials [33]Ikegawa S, Sperling AS, Ansuinelli M, et al. T-Charge™ manufacturing of the anti-BCMA CAR-T, durcabtagene autoleucel (PHE885), promotes expansion and persistence of CAR-T cells with high TCR repertoire diversity. Blood 2023; 142(Suppl. 1), 3469–3469. [58]Berdeja JG, Madduri D, Usmani SZ, et al. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a Phase 1b/2 open-label study. Lancet 2021; 398(10297), 314–324. [59]Bishop MR, Rosenblatt J, Dhakal B, et al. Phase 1 study of anitocabtagene autoleucel for the treatment of patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM): efficacy and safety with 34-month median follow-up. Blood 2024; 144, 4825.. These findings suggest that dose escalation trials will need to be performed with the rapidly generated CAR-T cells, as efficacious doses may depend on the disease indication or tumor associated environments. Although it is likely not feasible to perform a head-to-head comparison of CAR-T cells generated in a rapid process and conventional process due to additional confounding variables, this information would be beneficial to the ongoing development efforts in this space.

Regarding the solid tumor landscape, clinical efficacy with conventional CAR-T cells remains a challenge, with no current commercial products on the market. Due to the inefficiencies of CAR-T cell trafficking from the blood to the solid tumor site, it is possible that solid tumor indications could mandate higher infusion doses than what is currently required for hematologic indications, which could be difficult to achieve in a rapid process. However, the superior T cell phenotype resulting from a rapid or expedited process could be a benefit in enhancing CAR-T durability, which may be ultimately more advantageous in treating solid tumor indications. It remains to be explored if therapeutic combinations or novel TME-directed approaches could enable the successful entrance of rapid CAR-T cell products into the solid tumor space.

Quality control and release criteria

Despite the headway that has been achieved in shortening the autologous manufacturing process, bringing us closer to being able to treat patients faster with a higher quality DP, product release testing and compliance with global regulatory bodies encompasses an additional challenge to overcome. The implementation of a shorter manufacturing timeframe often eliminates the in-process culture washing and media exchanges which help to remove or dilute impurities from the DP, including residual viral vector or non-T cell populations. In order to meet defined product specifications with regard to product identify, safety and purity it will be critical to demonstrate that removal of any process related impurities can be achieved within a shortened manufacturing timeframe [26]Ayala Ceja M, Khericha M, Harris CM, et al. CAR-T cell manufacturing: major process parameters and next-generation strategies. J. Exp. Med. 2024; 221(2), e20230903. [60]Agliardi G, Dias J, Rampotas A, et al. Accelerating and optimising CAR-T-cell manufacture to deliver better patient products. Lancet Haematol. 2025; 12(1), e57–e67.. Logistically, this will require minimizing the concentration of raw materials used within the process and implementing additional wash steps during the harvest procedure.

Perhaps the largest concern for product release testing with an accelerated process is validation of product identity and potency. Currently, under standard manufacturing conditions, evaluation of CAR-Transgene expression is performed using a flow cytometric approach of surface protein expression or a PCR-based viral copy number assay to quantify the number of transcripts integrated into the host cell genome. These methodologies can reliably measure stable CAR expression which plateaus in a conventional 5–10 day process. However, the ability to reliably measure CAR expression 48–72 h post-transduction has proven to be challenging using existing, qualified flow cytometry methods. It has been previously reported that integration of lentivirally-delivered genetic material is accompanied by a delay of 2–3 days prior to detection which can be explained by integration of the transgene, translation of the mRNA transcript and trafficking of the CAR molecule to the T cell surface [61]Milone MC, O’Doherty U. Clinical use of lentiviral vectors. Leukemia 2018; 32(7), 1529–1541.. Additionally, previous reports of pseudotransduction and unstable CAR expression at these early time points have been identified as an area of concern, as these measurements may yield unreliable results for formulation and dosing [41]Ghassemi S, Durgin JS, Nunez-Cruz S, et al.Rapid manufacturing of non-activated potent CAR-T cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022; 6(2), 118–128.. With the advent of rapid processes, it is possible that additional orthogonal assays that are not reliant on surface CAR expression may need to be developed to facilitate product release under accelerated manufacturing timelines.

Additional safety release testing encompasses mycoplasma, endotoxin, and sterility testing to ensure the DP is free from harmful contaminants. Conventional sterility testing can require up to 14 days. There has been promising development surrounding rapid sterility testing using sensitive cytometry systems capable of detecting fluorescently labeled microorganisms or non-growth based 16S and 18S amplicon sequencing modalities which can significantly reduce this 14 day timeframe to several hours to days [62]Strutt JPB, Natarajan M, Lee E, et al. Machine learning-based detection of adventitious microbes in T-cell therapy cultures using long-read sequencing. Microbiol. Spect. 2023; 11(5), e01350-23. [63]Mohammadi M, Bauer A, Roseti D, et al. A rapid sterility method using solid phase cytometry for cell-based preparations and culture media and buffers. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 2023; 77(6), 498–513.. An additional solution encompasses an all-in-one approach to release testing in which multiple assays are performed in parallel using automated technology. An in-process QC technology platform, coined CellQ®, is currently deployed by Cellares to resolve manual QC processing bottlenecks associated with release testing and could be integrated into a rapid manufacturing setting. Additionally, this automated, high throughput platform can generate results using minimal sample volumes and reduce the need for any re-testing due to operator error. While these types of all-in-one QC platforms are enticing, they still rely heavily on the development of technologies that can reliably assess the critical parameters in a premature cell population, most challengingly CAR-T cell identity and potency.

Potency assays assessing CAR-T cell functionality inherently face the same challenges as CAR detection/identity assays given they rely on CAR-mediated recognition of tumor antigen which drives a cytotoxic T cell response. Currently, regulatory agencies recommend the development and utilization of orthogonal assays to measure potency including direct tumor cell killing and cytokine secretion prior to product release. Whether or not CAR-T cell cytotoxic performance or interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production at rapid harvest timepoints are representative of the DP attributes upon stable transgene integration remain an open question and active area of investigation.

In attempt to circumvent the challenges surrounding CAR detection and potency at early time points, an alternative strategy is to retain a subculture of the DP for a specified time period until flow cytometric approaches can be reliably used to estimate the dose before release of the DP. This approach does however add complexity to DP formulation and filling, QC release testing and pharmacy manual instructions. Additionally, with the recent development of rapid sterility methods, subculture techniques to confirm CAR identity could impose another bottleneck that delays DP release. Therefore, the development and validation of molecular-based analytical methods that can be reliably used at earlier stages in the manufacturing process may offer a preferable solution to detect accurate CAR+ cell numbers from a rapid process. In summary, acceleration of DP release requires innovative solutions that minimize sample volumes, employ automation, and implement novel methods to accurately identify CAR+ cells and report sterility with rapid turnaround time.

Decentralized manufacturing facilities

As previously mentioned, most pharmaceutical companies that have commercial CAR-T products have adopted a centralized manufacturing model in which the patient’s apheresis is shipped to a dedicated production facility to manufacture the DP. This model is preferred from a quality control and standardization perspective with less opportunity for production or method protocol variation. Additionally, these large-scale facilities are equipped to accommodate large numbers of manufacturing starts each day making them financially attractive options. However, centralized manufacturing designs can extend the V2V time given additional transportation times on both the front and back end of the process, while also mandating cryopreservation of the DP prior to re-infusion. Adoption of a regionalized production scheme in which a patient’s drug is manufactured relatively close to the infusion center would simplify the transport logistics and could potentially enable delivery of a fresh DP to the patient (Figure 1). Prior reports have demonstrated potential benefits of a fresh DP over its frozen counterpart including improved in vivo functionality and improved product quality [64]Maschan M, Caimi PF, Reese-Koc J, et al.Multiple site place-of-care manufactured anti-CD19 CAR-T cells induce high remission rates in B-cell malignancy patients. Nat. Commun. 2021; 12(1), 7200.Maschan M, Caimi PF, Reese-Koc J, et al.Multiple site place-of-care manufactured anti-CD19 CAR-T cells induce high remission rates in B-cell malignancy patients. Nat. Commun. 2021; 12(1), 7200. [65]Shah NN, Szabo A, Furqan F, et al. Adaptive manufacturing of LV20.19 CAR-T-cells for relapsed, refractory mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2023; 142(Suppl. 1), 1024–1024.. Additionally, a previous clinical study has demonstrated production feasibility in a decentralized model with a low frequency of manufacturing failures [64]Maschan M, Caimi PF, Reese-Koc J, et al.Multiple site place-of-care manufactured anti-CD19 CAR-T cells induce high remission rates in B-cell malignancy patients. Nat. Commun. 2021; 12(1), 7200.. While both scientific and clinical evidence support moving toward a more dispersed manufacturing paradigm, this shift is challenging for large cell therapy manufacturers to implement.

Unfortunately, regionalized, or decentralized models are subject to their own set of challenges that must be overcome to reap the benefits of this manufacturing model. As alluded to previously, this would require the infrastructure to support multiple manufacturing facilities strategically placed across the USA, Europe, and Asia to limit barriers to patient access. Moreover, it is critical that each independent site is aligned not only on the manufacturing process and corresponding batch records, but also the execution of release methods to ensure consistency in the drug product [66]Stroncek DF, Somerville RPT, Highfill SL. Point-of-care cell therapy manufacturing; it’s not for everyone. J. Transl. Med. 2022; 20(1), 34.. These efforts will require significant oversight and coordination, posing a significant CMC and Quality challenge. Specifically, instituting a quality organization to manage and resolve any deviations or OOSs that may arise across multiple sites represents a significant barrier to integration of this model. Additionally, despite the continued push for end-to-end process automation, at this time, semi-automated processes do still require hands-on operator time to oversee the process and perform necessary manipulations of the material [67]Shah NN, Johnson BD, Schneider D, et al. Bispecific anti-CD20, anti-CD19 CAR-T cells for relapsed B cell malignancies: a Phase 1 dose escalation and expansion trial. Nat. Med. 2020; 26(10), 1569–1575. [68]Aleksandrova K, Leise J, Priesner C, et al. Functionality and cell senescence of CD4/ CD8-selected CD20 CAR-T cells manufactured using the automated CliniMACS Prodigy® Platform. Trans. Med. Hemother. 2019; 46(1), 47–54. [69]Mock U, Nickolay L, Philip B, et al. Automated manufacturing of chimeric antigen receptor T cells for adoptive immunotherapy using CliniMACS Prodigy. Cytotherapy 2016; 18(8), 1002–1011. [70]Lock D, Mockel-Tenbrinck N, Drechsel K, et al. Automated manufacturing of potent CD20-directed chimeric antigen receptor T cells for clinical use. Hum. Gene Ther. 2017; 28(10), 914–925.. In a regionalized or de-centralized model, the manufacturing sites may be located in less metropolitan locations which could pose significant staffing challenges or mandate rigorous training programs to ensure operators are qualified to lead the manufacturing efforts.

Considering the future of cell therapy, adoption of a decentralized or point-of-care manufacturing setting would revolutionize patient access. In an idealized scenario, immediately after leukapheresis, a patient’s material would enter manufacturing on site eliminating the need for formulation and cryopreservation. If a rapid manufacturing process (<72 h) is employed in a near patient setting, the patient DP can be harvested and prepared for infusion within 4 days, plus the time required for the completion of rapid release testing. Adoption of this process can reduce the V2V time by at least 7 days—the time associated with transport plus the difference between conventional (6–12 day) and rapid (3 day) manufacturing (Figure 1) [71]Orentas RJ, Dropulić B, de Lima M. Place of care manufacturing of chimeric antigen receptor cells: opportunities and challenges. Semin. Hematol. 2023; 60(1), 20–24.. A reduction in V2V time has been demonstrated to have significant clinical implications on patient outcomes and predicted life expectancy gains following CAR-T treatment [20]Vadgama S, Pasquini MC, Maziarz RT, et al. ‘Don’t keep me waiting’: estimating the impact of reduced vein-to-vein time on lifetime US 3L+ LBCL patient outcomes. Blood Adv. 2024; 8(13), 3519–3527. [60]Agliardi G, Dias J, Rampotas A, et al. Accelerating and optimising CAR-T-cell manufacture to deliver better patient products. Lancet Haematol. 2025; 12(1), e57–e67.. Finally shortening of this timeframe could not only help limit disease progression and potentially mitigate the need for poorly tolerated bridging therapy, but may also help ensure that more patients become eligible for these life-saving treatments.

Drug product attributes and therapeutic benefit

Increased patient access is the primary clinical driver of the development of an accelerated manufacturing process, but the higher quality of the DP that results from a shorter ex vivo culture time may improve patient responses. Early preclinical and clinical data have shown that a shortened ex vivo culture time reduces terminal T cell differentiation and subsequent acquisition of a transcriptionally exhausted program [35]Yang J, He J, Zhang X, et al. Next-day manufacture of a novel anti-CD19 CAR-T therapy for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: first-in-human clinical study. Blood Cancer J. 2022; 12(7), 104. [41]Ghassemi S, Durgin JS, Nunez-Cruz S, et al.Rapid manufacturing of non-activated potent CAR-T cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022; 6(2), 118–128. [72]Ghassemi S, Nunez-Cruz S, O’Connor RS, et al. Reducing ex vivo culture improves the antileukemic activity of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018; 6(9), 1100–1109.. Additionally, cells harvested under restricted cultivation conditions demonstrate improved anti-tumor functionality, increased proliferative potential, and expanded in vivo persistence, all of which are indicative of attributes of a naïve/central memory T cell.

Previous preclinical investigations using patient material have demonstrated that CD19-targeting CAR-T cells harvested at earlier time points (3 or 5 days) have increased anti-leukemic activity in a murine xenograft model of ALL as compared to those harvested at later time points (9 days) [72]Ghassemi S, Nunez-Cruz S, O’Connor RS, et al. Reducing ex vivo culture improves the antileukemic activity of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018; 6(9), 1100–1109.Ghassemi S, Nunez-Cruz S, O’Connor RS, et al. Reducing ex vivo culture improves the antileukemic activity of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018; 6(9), 1100–1109.. Effectively, sub-therapeutic doses of earlier harvest CAR-T cells were able to induce disease remission in this model. Phenotypically, longer culture periods also enriched for effector CD8+ T cells as defined by the phenotypic signature CD45RO+, CCR7- whereas naïve-like cells were more prevalent after shorter ex vivo culture durations. Additionally, CAR-T cells harvested after only 3 days in culture showed increased fold expansion upon tumor antigen exposure in vitro, as well as long term persistence in vivo [72]Ghassemi S, Nunez-Cruz S, O’Connor RS, et al. Reducing ex vivo culture improves the antileukemic activity of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018; 6(9), 1100–1109.Ghassemi S, Nunez-Cruz S, O’Connor RS, et al. Reducing ex vivo culture improves the antileukemic activity of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018; 6(9), 1100–1109..

In the clinical space, Bristol Myers Squibb initiated a Phase 1 study investigating their accelerated NEX-T 5–6 day CAR-T manufacturing process. The next-generation BCMA asset, BMS-986354, illustrates a significant enrichment in central memory (CD45RA-, CCR7+) cells in the DP as compared to the control CAR-T, orcabtagene autoleucel (orva cel) as well as increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α [43]Costa LJ, Kumar SK, Atrash S, et al. Results from the first Phase 1 clinical study of the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) Nex T chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy CC-98633/BMS-986354 in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). Blood 2022; 140(Suppl. 1), 1360–1362.Costa LJ, Kumar SK, Atrash S, et al. Results from the first Phase 1 clinical study of the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) Nex T chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy CC-98633/BMS-986354 in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). Blood 2022; 140(Suppl. 1), 1360–1362.. Patients enrolled in the dose escalation trial received 20–80 × 106 CAR+ T cells, a 2.5–7.5-fold reduction in dose, relative to the orva cel trials. Despite receiving a fraction of the standard manufacturing process dose, both products demonstrate comparable post-infusion expansion, suggesting that the NEX-T products have increased proliferative potential and persistence. Finally, from a safety and efficacy perspective, BMS-986354 illustrates an overall response rate of 95% with an accompanying profile of low-grade CRS and neurotoxicity [43]Costa LJ, Kumar SK, Atrash S, et al. Results from the first Phase 1 clinical study of the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) Nex T chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy CC-98633/BMS-986354 in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). Blood 2022; 140(Suppl. 1), 1360–1362.Costa LJ, Kumar SK, Atrash S, et al. Results from the first Phase 1 clinical study of the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) Nex T chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy CC-98633/BMS-986354 in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). Blood 2022; 140(Suppl. 1), 1360–1362.. The reduction in therapeutic dose may explain the low-grade adverse events and further reinforce the clinical advantages to adopting a rapid process.

Novartis has also developed a rapid (<2-day) manufacturing process coined, T-Charge, which has been implemented in DLBCL, CLL, ALL, and MM indications [33]Ikegawa S, Sperling AS, Ansuinelli M, et al. T-Charge™ manufacturing of the anti-BCMA CAR-T, durcabtagene autoleucel (PHE885), promotes expansion and persistence of CAR-T cells with high TCR repertoire diversity. Blood 2023; 142(Suppl. 1), 3469–3469.Ikegawa S, Sperling AS, Ansuinelli M, et al. T-Charge™ manufacturing of the anti-BCMA CAR-T, durcabtagene autoleucel (PHE885), promotes expansion and persistence of CAR-T cells with high TCR repertoire diversity. Blood 2023; 142(Suppl. 1), 3469–3469. [34]Dickinson MJ, Barba P, Jager U, et al. A novel autologous CAR-T therapy, YTB323, with preserved T-cell stemness shows enhanced CAR-T-cell efficacy in preclinical and early clinical development. Cancer Discov. 2023; 13(9), 1982–1997.Dickinson MJ, Barba P, Jager U, et al. A novel autologous CAR-T therapy, YTB323, with preserved T-cell stemness shows enhanced CAR-T-cell efficacy in preclinical and early clinical development. Cancer Discov. 2023; 13(9), 1982–1997.. Initial clinical evaluation of safety and preliminary efficacy of the CD19-targeted CAR, YTB323, are extremely promising. Relative to the traditionally manufactured product, tisagenlecleucel, YTB323 retained a higher frequency of naïve and stem cell memory T cell subsets which was further reinforced by stem-like gene signatures present in bulk and scRNA-seq analyses. Functionally, rapidly manufactured cells demonstrate better killing capability upon repetitive stimulation suggesting these cells have increased survival capacity and resistance to acquisition of an exhausted transcriptome. In line with BMS-986354, the pharmacokinetics of YTB323 also illustrate enhanced proliferative potential in vivo as compared to tisgenlecleucel despite being administered at a 25-fold lower dose, as well as a desirable safety profile [34]Dickinson MJ, Barba P, Jager U, et al. A novel autologous CAR-T therapy, YTB323, with preserved T-cell stemness shows enhanced CAR-T-cell efficacy in preclinical and early clinical development. Cancer Discov. 2023; 13(9), 1982–1997.. Analogously, BCMA-targeted CAR-T cells manufactured with the T-Charge platform termed, PHE885, illustrate strong clinical efficacy, self-renewal capacity and long-term persistence at 6 months of follow-up [33]Ikegawa S, Sperling AS, Ansuinelli M, et al. T-Charge™ manufacturing of the anti-BCMA CAR-T, durcabtagene autoleucel (PHE885), promotes expansion and persistence of CAR-T cells with high TCR repertoire diversity. Blood 2023; 142(Suppl. 1), 3469–3469.. Furthermore, given the reduced V2V time, less than 30% of patients required bridging therapy prior to CAR-T infusion [73]Sperling AS, Nikiforow S, Derman B, et al. P1446: Phase 1 study data update of PHE885, a fully human BCMA-directed CAR-T cell therapy manufactured using the t-chargetm platform for patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) multiple myeloma (MM). HemaSphere 2022; 6, 1329–1330.. Collectively, the early Phase 1 findings discussed in this section support the continued investment in developing rapid processes across hematologic disease indications.

Several other companies have made significant headway in this space including Kite/Tmunity, AstraZeneca/Gracell, Precigen, and Hrain Biotechnology, all leading Phase 1 trials utilizing accelerated manufacturing (Table 2). Many of the DP attributes echo the previous reports highlighting the robustness of rapid manufacturing across varying processes, tumor targets, and disease indications. Despite most investigations remaining largely focused on hematologic malignancies, there has been an expansion of cell therapies into solid tumors (ovarian, triple negative breast) and autoimmune indications (systemic lupus erythematosus) [38]Liao JB, Stanton SE, Chakiath M, et al. Phase 1/1b study of PRGN-3005 autologous UltraCAR-T cells manufactured overnight for infusion next day to advanced stage platinum resistant ovarian cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023; 41(16 Suppl.), 5590–5590. [53]Chan T, Scott SP, Du M, et al. Preclinical evaluation of Prgn-3007, a non-viral, multigenic, autologous ROR1 Ultracar-T® therapy with novel mechanism of intrinsic PD-1 blockade for treatment of hematological and solid cancers. Blood 2021; 138(Suppl. 1), 1694–1694. [74]Du J, Qiang W, Lu J, et al. Updated results of a Phase 1 open-label single-arm study of dual targeting BCMA and CD19 Fastcar-T cells (GC012F) as first-line therapy for transplant-eligible newly diagnosed high-risk multiple myeloma. Blood 2023; 142(Suppl. 1), 1022–1022.. Solid tumors have remained a challenge for CAR-T cell therapy for nearly a decade, and it remains unclear if heightened cellular potency will be sufficient to overcome hurdles including T cell trafficking and suppressive tumor microenvironments. However, if combined with an optimized CAR design and appropriate manufacturing strategies, the field is hopeful that this approach could improve clinical responses and bolster cell therapy expansion into solid tumor malignancies.

Translation insights

Rapid manufacturing processes are one approach to reduce patient V2V time and increase the accessibility of cell therapies. In addition to the clinical benefits including reduced opportunity for disease progression and generation of a higher quality DP, there are additional benefits of a rapid process from a manufacturing perspective. Reducing the time required to generate a clinical dose will increase manufacturing capacity enabling a scale up of the number of patients who can be manufactured per unit time. For example, cutting the manufacturing time in half will double the number of patients who can be manufactured in any given facility. This not only offsets facility costs on a per patient basis but will also reduce labor costs of operators required to perform critical manufacturing steps and provide oversight to the process. The extensive list of incentives for pursuing a rapid process have inspired key players in the cell therapy landscape to continue tackling the challenges preventing widespread implementation of a rapid process. These challenges include controlling for DP purity, achieving an efficacious clinical dose without a cell expansion phase and rapid, reliable release methods. Accurate characterization of the DP at an early timepoint is difficult with the current set of acceptable release assays, however, developing and qualifying new technologies capable of predicting stable CAR expression from a transient readout may be able to address these challenges. Alternatively, redesigning the dosing strategy could also alleviate these issues. Purity of the DP without additional washes during the process raises concerns for heightened lentiviral, non-T cell populations, and other process related impurities. However, rigorous washing during the formulation process as well as the development of increased sensitivity assays to detect these contaminants may help alleviate surrounding concerns. Finally, regarding dosing guidelines, it is likely that advancements in CAR design and armoring strategies will enable lower efficacious clinical doses that can be readily achieved with a rapid process, making treating solid tumors indications more feasible.

Conclusion

CAR-T cell therapy has made a profound impact on patients’ lives in the last decade, however, there remains an unmet clinical need–to reduce the time to administration and increase the number of patients who can successfully receive this form of therapy. One component of the V2V time is the time required to generate the DP ex vivo. Recent advances in cell manufacturing have demonstrated small scale feasibility and increased clinical efficacy of CAR-T cells generated within 72 h. However, widespread adoption of a rapid process will require innovative process and analytical development efforts, regionalized manufacturing models that enable the use of fresh apheresis, as well as early and more frequent interaction with global regulatory agencies. In addition, the early preclinical and clinical data suggesting that rapidly manufactured cells are inherently more potent may warrant further clinical investigation into defining an efficacious dose with a heightened awareness of potential toxicities that may arise. Despite the current financial and logistical challenges, rapid processes can significantly increase manufacturing capacity while the adoption of automated platforms can further increase scalability and reduce labor costs to justify the upfront investment.

References

1. First-ever CAR-T-cell therapy approved in US. Cancer Discov. 2017; 7(10), OF1–OF1. Crossref

2. Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018; 378(5), 439–448. Crossref

3. Schuster SJ, Bishop MR, Tam CS, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019; 380(1), 45–56. Crossref

4. Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR-T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017; 377(26), 2531–2544. Crossref

5. Locke FL, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel as second-line therapy for large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022; 386(7), 640–654. Crossref

6. Shah BD, Ghobadi A, Oluwole OO, et al. KTE-X19 for relapsed or refractory adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: Phase 2 results of the single-arm, open-label, multicentre ZUMA-3 study. Lancet 2021; 398(10299), 491–502. Crossref

7. Abramson JS, Palomba ML, Gordon LI, et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. Lancet 2020; 396(10254), 839–852. Crossref

8. Munshi NC, Anderson Jr LD, Shah N, et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021; 384(8), 705–716. Crossref

9. San-Miguel J, Dhakal B, Yong K, et al. Cilta-cel or standard care in lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023; 389(4), 335–347. Crossref

10. Roddie C, Sandhu KS, Tholouli E, et al. Obecabtagene autoleucel in adults with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024; 391(23), 2219–2230. Crossref

11. Posey AD Jr, Young RM, June CH. Future perspectives on engineered T cells for cancer. Trends Cancer 2024; 10(8), 687–695. Crossref

12. Elsallab M, Ellithi M, Lunning MA, et al.Second primary malignancies after commercial CAR-T-cell therapy: analysis of the FDA Adverse Events Reporting System. Blood 2024; 143(20), 2099–2105. Crossref

13. Khare S, Williamson S, O’Barr B, et al. Sociodemographic factors influencing access to chimeric antigen T-cell receptor therapy for patients with non-hodgkin lymphoma. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2025; 25(2), e120–e125. Crossref

14. Ghilardi G, Williamson S, Pajarillo R, et al. CAR-T-cell immunotherapy in minority patients with lymphoma. NEJM Evid. 2024; 3(4), EVIDoa2300213. Crossref

15. Hernandez I, Prasad V, Gellad WF. Total costs of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell immunotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2018; 4(7), 994–996. Crossref

16. Karschnia P, Miller KC, Yee AJ et al. Neurologic toxicities following adoptive immunotherapy with BCMA-directed CAR-T cells. Blood 2023; 142(14), 1243–1248. Crossref

17. Ehsan H, Ahmed F, Moyo TK, et al. Real-world analysis of barriers to timely administration of chimeric antigen receptor T-Cell (CART) therapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Blood 2023; 142(Suppl. 1), 7393–7393. Crossref

18. Sureda A, El Adam S, Yang S, et al. Logistical challenges of CAR-T-cell therapy in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a survey of healthcare professionals. Future Oncol. 2024; 20(36), 2855–2868. Crossref

19. Tully S, Feng Z, Grindod K, et al. Impact of increasing wait times on overall mortality of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in large B-cell lymphoma: a discrete event simulation model. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2019; 3, 1–9. Crossref

20. Vadgama S, Pasquini MC, Maziarz RT, et al. ‘Don’t keep me waiting’: estimating the impact of reduced vein-to-vein time on lifetime US 3L+ LBCL patient outcomes. Blood Adv. 2024; 8(13), 3519–3527. Crossref

21. Tyagarajan S, Spencer T, Smith J. Optimizing CAR-T cell manufacturing processes during pivotal clinical trials. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020; 16, 136–144. Crossref

22. Pavlic J, Fury B, Mayo J, et al. Optimizing CAR-T cell therapy: reducing manufacturing time and examining T cell memory phenotypes in B cell lymphoma. Blood 2024; 144(Suppl. 1), 7254–7254. Crossref

23. Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Torabi-Parizi P, et al. Central memory self/tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells confer superior antitumor immunity compared with effector memory T cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2005; 102(27), 9571–9576. Crossref

24. Gattinoni L, Klebanoff CA, Palmer DC, et al. Acquisition of full effector function in vitro paradoxically impairs the invivo antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2005; 115(6), 1616–1626. Crossref

25. Sommermeyer D, Hudecek M, Kosasih PL, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells derived from defined CD8+ and CD4+ subsets confer superior antitumor reactivity in vivo. Leukemia 2016; 30(2), 492–500. Crossref

26. Ayala Ceja M, Khericha M, Harris CM, et al. CAR-T cell manufacturing: major process parameters and next-generation strategies. J. Exp. Med. 2024; 221(2), e20230903. Crossref

27. Alizadeh D, Wong RA, Yang X, et al. IL15 enhances CAR-T cell antitumor activity by reducing mTORC1 activity and preserving their stem cell memory phenotype. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019; 7(5), 759–772. Crossref

28. Cieri N, Camisa B, Cocchiarella F, et al.IL-7 and IL-15 instruct the generation of human memory stem T cells from naive precursors. Blood 2013; 121(4), 573–584. Crossref

29. Xu Y, Zhang M, Ramos CA, et al. Closely related T-memory stem cells correlate with in vivo expansion of CAR.CD19-T cells and are preserved by IL-7 and IL-15. Blood 2014; 123(24), 3750–3759. Crossref

30. Hanley PJ. Fresh versus frozen: effects of cryopreservation on CAR-T cells. Mol. Ther. 2019; 27(7), 1213–1214. Crossref

31. Brezinger-Dayan K, Itzhaki O, Melnichenko J, et al. Impact of cryopreservation on CAR-T production and clinical response. Front. Oncol. 2022; 12, 1024362. Crossref

32. Panch SR, Srivastava SK, Elavia N, et al. Effect of cryopreservation on autologous chimeric antigen receptor T cell characteristics. Mol. Ther. 2019; 27(7), 1275–1285. Crossref

33. Ikegawa S, Sperling AS, Ansuinelli M, et al. T-Charge™ manufacturing of the anti-BCMA CAR-T, durcabtagene autoleucel (PHE885), promotes expansion and persistence of CAR-T cells with high TCR repertoire diversity. Blood 2023; 142(Suppl. 1), 3469–3469. Crossref

34. Dickinson MJ, Barba P, Jager U, et al. A novel autologous CAR-T therapy, YTB323, with preserved T-cell stemness shows enhanced CAR-T-cell efficacy in preclinical and early clinical development. Cancer Discov. 2023; 13(9), 1982–1997. Crossref

35. Yang J, He J, Zhang X, et al. Next-day manufacture of a novel anti-CD19 CAR-T therapy for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: first-in-human clinical study. Blood Cancer J. 2022; 12(7), 104. Crossref

36. Chen X, Ping Y, Li L, et al. CD19/BCMA dual-targeting Fastcar-T GC012F for patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an update. Blood 2023; 142(Suppl. 1), 6847–6847. Crossref

37. Ahmad S, Chan T, Sayed A, et al. 232 Non-viral engineered next generation CD19 UltraCAR-T with membrane bound IL-15 (mbIL15) and PD-1 blockade preserves stem cell memory/naïve phenotype and enhances anti-tumor efficacy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024; 12(Suppl. 2), A266–A266. Crossref

38. Liao JB, Stanton SE, Chakiath M, et al. Phase 1/1b study of PRGN-3005 autologous UltraCAR-T cells manufactured overnight for infusion next day to advanced stage platinum resistant ovarian cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023; 41(16 Suppl.), 5590–5590. Crossref

39. Wang H, Tsao ST, Xiong Q, et al. 621MO Preclinical study of DASH CAR-T cells manufactured in 48 hours. Ann. Oncol. 2022; 33, S828. Crossref

40. Deng T, Deng Y, Tsao ST, et al. Rapidly-manufactured CD276 CAR-T cells exhibit enhanced persistence and efficacy in pancreatic cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2024; 22(1), 633. Crossref

41. Ghassemi S, Durgin JS, Nunez-Cruz S, et al.Rapid manufacturing of non-activated potent CAR-T cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022; 6(2), 118–128. Crossref

42. Anaya D, Kwong B, Park S, et al. Development of Ingenui-T, a rapid autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T manufacturing solution using whole blood, for treatment of autoimmune disease. Cytotherapy 2024; 26(6 Suppl.), S9. Crossref

43. Costa LJ, Kumar SK, Atrash S, et al. Results from the first Phase 1 clinical study of the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) Nex T chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy CC-98633/BMS-986354 in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). Blood 2022; 140(Suppl. 1), 1360–1362. Crossref

44. Wang YI, Hao YN, Shen MY, et al. The expression of LDL-R in CD8+ T cells serves as an early assessment parameter for the production of TCR-T cells. In Vivo 2023; 37(6), 2480–2489. Crossref

45. Bonacina F, Moregola A, Svecla M, et al. The low-density lipoprotein receptor-mTORC1 axis coordinates CD8+ T cell activation. J. Cell Biol. 2022; 221(11). Crossref

46. Corrado M, Pearce EL. Targeting memory T cell metabolism to improve immunity. J. Clin. Invest. 2022; 132(1), e148546. Crossref

47. Zheng W, O’Hear CE, Alli R, et al. PI3K orchestration of the in vivo persistence of chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells. Leukemia 2018; 32(5), 1157–1167. Crossref

48. Turtle CJ, Hanafi LA, Berger C, et al.CD19 CAR-T cells of defined CD4+:CD8+ composition in adult B cell ALL patients. J. Clin. Invest. 2016; 126(6), 2123–2138. Crossref

49. Fraietta JA, Lacey SF, Orlando EJ, et al. Determinants of response and resistance to CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat. Med. 2018; 24(5), 563–571. Crossref

50. Gattinoni L, Klebanoff CA, Restifo NP. Paths to stemness: building the ultimate antitumour T cell. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012; 12(10), 671–684. Crossref

51. Sabatino M, Hu J, Sommariva M, et al. Generation of clinical-grade CD19-specific CAR-modified CD8+ memory stem cells for the treatment of human B-cell malignancies. Blood 2016; 128(4), 519–528. Crossref