Genetic integrity testing of genome-edited pluripotent stem cell lines used for cell therapy applications

Cell & Gene Therapy Insights 2025; 11(10), 1291–1310

DOI: 10.18609/cgti.2025.151

Human pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) can be the starting point for powerful tailored allogeneic cell therapies. Genetically engineered clonal lines constitute the basis for custom production of defined effector lineages, which enable targeting of otherwise difficult-to-treat diseases, e.g. in the fields of immune-oncology, neuronal and metabolic disorders. Fully characterized starting material is essential for advanced therapy medicinal product (ATMP) manufacturing, and therefore it is also essential to perform a comprehensive and thorough genetic integrity validation of PSC starting material during and after genetic engineering.

Genome editing of PSCs for clinical applications is usually multifactorial. Therapeutic edits include amelioration of cell function by inactivation of suppressive factors, enhancing disease-relevant functions by e.g. expression of chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), or introduction of immune shielding modifications for long-term persistence of therapeutic cells. Besides generation of the desired edit, genome engineering can lead to accidental acquisition of genetic aberrations or unwanted editing-related changes. In this article, we discuss the rationale of genetic integrity testing approaches for gene-edited PSCs, and how these procedures allow identification of thoroughly characterized, ON-target genome-edited PSC clones serving as starting material for safe and effective cell therapy products.

Introduction

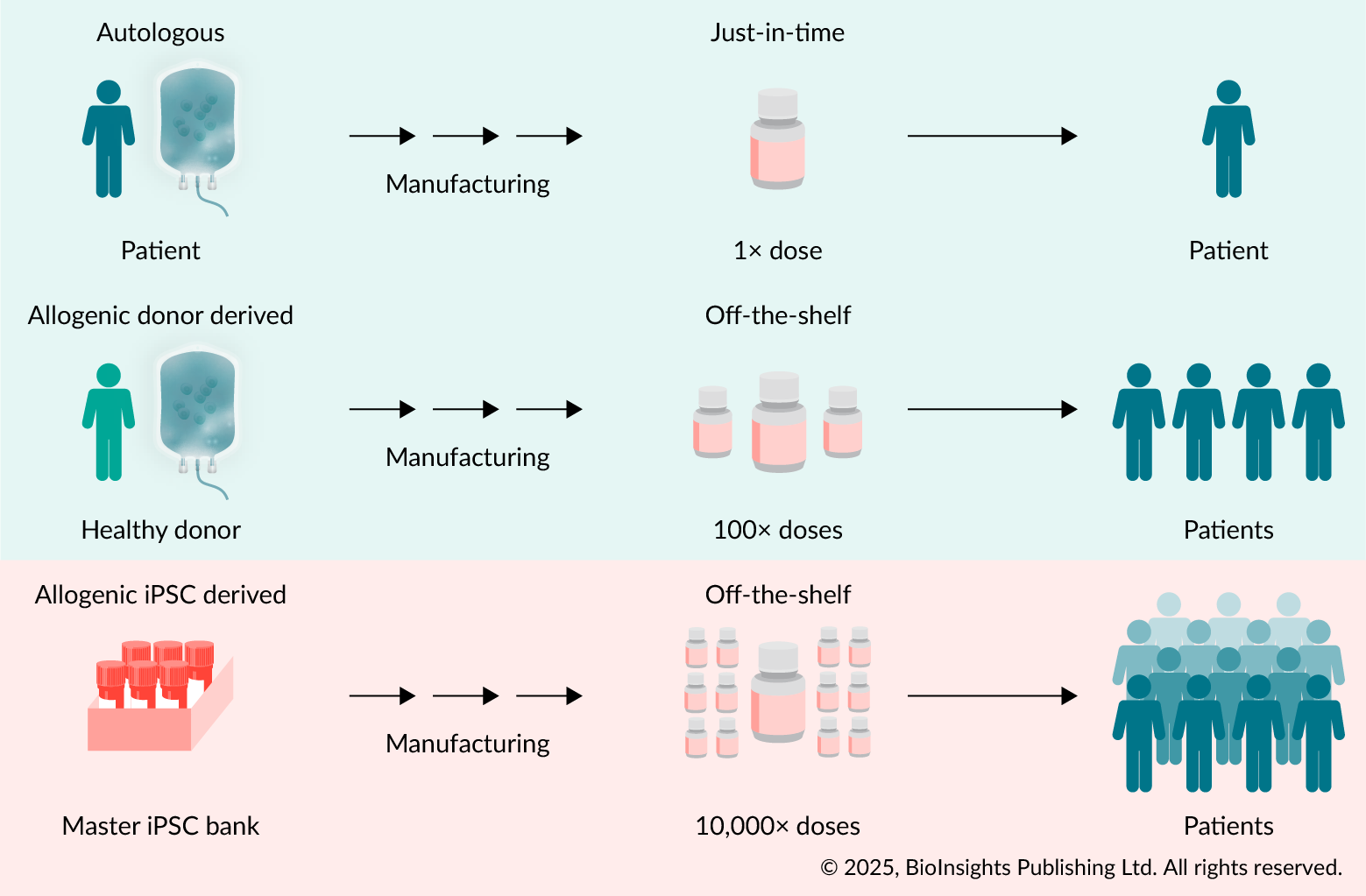

Autologous cell therapies using patient-derived starting material can be a highly efficacious way to treat leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma or B-cell mediated autoimmune diseases [1]Patel KK, Tariveranmoshabad M, Kadu S, Shobaki N, June C. From concept to cure: the evolution of CAR-T cell therapy. Mol. Ther. 2025; 33, 2123–2140. [2]Schett G, Müller F, Taubmann J, et al. Advancements and challenges in CAR T cell therapy in autoimmune diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2024; 20, 531–544.. However, cells for this treatment approach are difficult to manufacture and commercialization is challenging due to limited patient cell availability, limited scalability and cumbersome logistics resulting in very high manufacturing costs. Allogeneic, healthy donor-derived cell therapy approaches can overcome many of these problems and can be prepared off-the-shelf. However, they face challenges due to overall limited cell yields and immune incompatibilities between donor and recipients (Figure 1).

The development of directed and scalable differentiation procedures for the generation of therapeutic cell types from pluripotent stem cells (PSCs: embryonic stem cells or induced pluripotent stem cells) has opened a wide array of potential therapeutic avenues [3]Yu J, Thomson JA. Pluripotent stem cell lines. Genes Dev. 2008; 22, 1987–1997. [4]Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006; 126, 663–676. [5]Yamanaka S. Pluripotent stem cell-based cell therapy—promise and challenges. Cell Stem Cell 2020; 27, 523–53.. Due to their unlimited expansion potential, allogeneic PSC-derived products help to overcome above-mentioned bottlenecks. Well-characterized master cell banks allow mass-manufacturing of homogeneous cell therapy products and can provide off-the-shelf doses for many patients (Figure 1). Major benefits of allogeneic PSC-derived cell therapy products lie in reduced manufacturing complexity (no dedicated patient material required for the manufacturing) and in its versatility, in which a single platform is suitable for manufacturing multiple cell types for various diseases. As a testimony for the significance of cell therapy approaches, by December 2024 a total of 116 approved clinical trials using allogeneic PSC-derived cell products have been registered [6]Kirkeby A, Main H, Carpenter M. Pluripotent stem-cell-derived therapies in clinical trial: a 2025 update. Cell Stem Cell 2025; 32, 10–37..

| Figure 1. Different cell therapy applications. |

|---|

|

(Top) Autologous approaches use patient cells with their inherent perfect immune-match. Manufacturing is personalized and serves one patient at a time. (Middle) Allogeneic healthy donor derived cells serve as off-the-shelf products. However, due to limited expandability and due to donor immune signatures, they have a limited range of potential patients. (Bottom) Allogeneic PSC-derived cell therapy products can be expanded as validated master cell banks, can be genetically engineered to e.g., enhance effector function or to avoid host immune responses, can be off-the-shelf differentiated into required effector cells, making them available to a vast number of patients and disease applications. © 2025, BioInsights Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved. |

PSC-derived cell therapy products have applicability in many disease areas [7]Deuse T, Schrepfer S. Progress and challenges in developing allogeneic cell therapies. Cell Stem Cell. 2025; 32, 513–528.. Unmodified PSC products, however, often have limited applicability due to immune-restrictions (allograft rejection) or limited functionality. Most applications require starting material with genetic modifications adapted to the target disease. For example, in immune oncology-based applications using e.g. PSC-derived macrophages, T cells or NK cells, differentiated effector cells have a strongly improved therapeutic effect when expressing chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), which drive specific recognition and killing of target cells [8]Paasch D, Meyer J, Stamopoulou A, et al. Ex vivo generation of CAR macrophages from hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells for use in cancer therapy. Cells 2022; 11, 994. [9]Hu X, Beauchesne P, Wang C, et al. Hypoimmune CD19 CAR T cells evade allorejection in patients with cancer and autoimmune disease. Cell Stem Cell 2025; 32, 1356–1368.e4. [10]Wang X, Zhang Y, Jin L, et al. An iPSC-derived CD19/BCMA CAR-NK therapy in a patient with systemic sclerosis. Cell 2025; 188, 4225–4238.e12.. Also, PSC-derived immune cells have been shown to benefit from overexpression of accessory factors adapted to the respective therapeutic program, e.g. by overexpression of receptors, chemokines or cytokines to enhance iNK-based tumour therapies [11]Fukutani Y, Kurachi K, Torisawa YS, et al. Human iPSC-derived NK cells armed with CCL19, CCR2B, high-affinity CD16, IL-15, and NKG2D complex enhance anti-solid tumor activity. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025; 16, 373.. Importantly, if repeat-dosing or long-term engraftment is the envisioned clinical regime, recognition and clearance of grafted cells can be reduced (or eliminated). This is particularly important if PSC-derived effector cells are meant to persist in the patient’s body (for instance in cell therapy targeting type 1 diabetes), in which grafted PSC-derived islet cells not only need to persist and function over many years despite alloimmunity, but in which especially beta cells also must be protected from persistent autoimmunity [12]Lanza R, Russell DW, Nagy A. Engineering universal cells that evade immune detection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019; 19, 723–733. [13]Vantyghem MC, de Koning EJP, Pattou F, Rickels MR. Advances in β-cell replacement therapy for the treatment of type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2019; 394, 1274–1285..

Designated PSC starting material must be well-characterized and its genetic stability validated since PSCs are known to accumulate genetic aberrations in culture. This has been previously reviewed in-depth in Cell & Gene Therapy Insights [14]Zanella F, Narcu R. Genetic stability of hPSCs and considerations for cell therapy. Cell & Gene Therapy Insights 2024; 10, 159–170.. Our article aims to highlight the specific challenges and considerations for genetic integrity testing of PSCs after genome engineering. We address how to ensure high quality gene-edited PSC starting material for allogeneic advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs).

Genetic engineering of PSCs

Our insight article restricts the discussion to cut-and-repair approaches and will not cover base or prime editing considerations. Most genome engineering approaches use Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) based systems to generate targeted DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) [15]Pacesa M, Pelea O, Jinek M. Past, present, and future of CRISPR genome editing technologies. Cell 2024; 187, 1076–1100.. Such DSBs will be repaired by cell endogenous repair pathways. In absence of a homologous donor template, break points will be re-joined by one of the predominant and fast-acting end-joining pathways: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), microhomology mediated end joining (MMEJ) or polymerase theta mediated end joining [16]Gelot C, Magdalou I, Lopez BS. Replication stress in mammalian cells and its consequences for mitosis. Genes 2015; 6, 267–298.. End joining pathways predominantly result in a precise repair outcome. However, due to continued CRISPR ON-target activity, insertions or deletions (indels) can arise when the repair machinery gets exhausted, with their size depending on the respective end-joining pathway (in most cases less than 10 nucleotides) This is a useful end-result if functional disruption of a target gene is desired (knock-out, KO) since any exon-based indel non-divisible by three will invariably translate to a functionally inactivated protein.

If a homologous donor is presented at the DSB, homology dependent repair (HDR) can occur, leading to precise insertion of the custom transgene repair cassette (knock-in, KI) [17]Haider S, Mussolino C. Fine-tuning homology-directed repair (HDR) for precision genome editing: current strategies and future directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025; 26, 4067.. This procedure allows generation of cells with the potential to (over-) express any kind of beneficial factor to help effector cells better tackling its respective disease type, or to establish immune evasion if required. Unlike with, for example, largely random lentiviral vector insertions, overexpression from a pre-defined locus will result in a better controlled outcome.

Before starting the editing procedure, reagents for generation of the DSBs should be carefully pre-selected. This, in particular, applies to the target specific single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) that are responsible to target-specifically recruit the nuclease and to ultimately generate a single specific DSB. Several bioinformatic tools exist to select ‘good’over ‘bad’ sgRNA choices [18]Liu G, Zhang Y, Zhang T. Computational approaches for effective CRISPR guide RNA design and evaluation. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020; 18, 35–44.. The output is driven by potential off-targeting events based on sequence similarity and gaps in the protospacer-target pairing. Those algorithms currently do not provide extensive information for ON-target efficiency or in cellulo effects, however, reliably identify guides recognizing almost identical regions with a high risk for OFF-targeting.

It is important to define two phases when dealing with potential OFF-targeting. After Bioinformatic selection, the first step is experimental OFF-target nomination to evaluate the precision of the editing spectrum of selected sgRNAs. The second step applies the nomination and applies this knowledge to validate absence of potential off-targeting post edit. As such, sgRNAs are initially selected using in silico approaches (CRISPOR, Cas-OFFinder or similar) to ensure minimal collateral editing propensity [19]Guo C, Ma X, Gao F, Guo Y. Off-target effects in CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023; 11, 1143157.Guo C, Ma X, Gao F, Guo Y. Off-target effects in CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023; 11, 1143157.. In the subsequent experimental step, proper OFF-target nomination can be performed in vitro, where isolated genomic DNA is treated with RNA-complexed CRISPR effector nucleases, and any cut (ON- or OFF-target) can be identified by short read WGS (e.g. Digenome-SEQ) [20]Kim D, Kang BC, Kim JS. Identifying genome-wide off-target sites of CRISPR RNA-guided nucleases and deaminases with Digenome-SEQ. Nat. Protoc. 2021; 16, 1170–1192. or targeted sequencing (e.g. BreakTag) [21]Longo GMC, Sayols S, Kotini AG, et al. Linking CRISPR–Cas9 double-strand break profiles to gene editing precision with BreakTag. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024; 43, 608–622.. The isolated genomic DNA is digested in vitro in absence of chromatin or cellular compartments, and any digestion pattern most likely represents over-digestion due to over-accessibility of target regions. De-risking a worst-case scenario of potential OFF-targeting and starting from a ‘maximum damage’scenario can be judged preferable and less prone to miss events in later analysis of isolated clonal lines. In cellulo nomination methods treat cells with the selected RNPs, and ON- and OFF-target DSBs are mapped in situ by ligation of indexing adapters (recent approaches include CHANGE-Seq, GUIDE-Seq, CAST-Seq or Uncover-Seq) [19]Guo C, Ma X, Gao F, Guo Y. Off-target effects in CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023; 11, 1143157.Guo C, Ma X, Gao F, Guo Y. Off-target effects in CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023; 11, 1143157.. The above-mentioned in cellulo assays investigate nucleases cutting the actual chromatinized template and possibly are not prone to over-digestion, better mimicking the actual situation in the cells. The enzymatic ligation of index-adaptors could, however, present a limiting factor to nomination of the full set of potential OFF-targets. The FDA does not specify a preferred method for OFF-target discovery, however, emphasizes the importance of OFF-target analysis/nomination to ensure safety and efficacy of CRISPR-based therapies. Once the nomination procedure has been accomplished, the dataset will serve as the basis for the subsequent OFF-target validation procedure. Post edit, any nominated potential OFF-target will be validated, i.e. absence thereof ensured in the final clonal line. This procedure preferentially uses deep targeted sequencing of the nominated sites (see section 4 of ‘Genetic integrity and quality assurance’).

After genome engineering, PSC clonal lines with the desired ON-target edit need to be identified and characterized. Although straightforward to screen for, it is important to emphasise that perfect ON-target editing might not be the predominant engineering outcome. It is important to screen for potential accompanying OFF-targeting events. Precise genetic engineering of PSCs with CRISPR is a well-established and reliable technology platform. However, also due to the action of cellular DNA repair pathways, cell-inherent events can add a certain unpredictability to the outcome of gene editing. For example, evidence has accumulated over the past years that DNA repair pathways can create genomic rearrangements, globally and as well in the inserted homology dependent repair templates (HDRTs) [22]Teboul L, Herault Y, Wells S, Qasim W, Pavlovic G. Variability in genome editing outcomes: challenges for research reproducibility and clinical safety. Mol. Ther. 2020; 6, 1422–1431.. Hence, a key element when gene-editing PSCs is to identify clonal lines with the desired ON-target edit and that are free of unwanted editing events.

Potential genetic aberrations post gene editing

OFF-targeting and formation of indels

Depending on the nuclease, most CRISPR-based target recognition occurs via a 18–25 nucleotide protospacer sequence. Perfect matching, coupled to presence of a defined nuclease-specific protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) is required for DNA cleavage. However, certain mismatch conditions in the protospacer-target base pairing can be tolerated by the nuclease and unwanted genomic loci can be affected (OFF-targets). Therefore, it is critically important to select the best suited guide with minimum predicted OFF-targeting potential. Noteworthy, any potential OFF-target site with >4 mismatches or with larger gaps in the protospacer-target pairing is considered having only a limited risk for OFF-targeting. Bioinformatic tools can nominate potential genome-wide off-target indels for each selected sgRNA, however, overall final editing outcomes with the chosen sgRNA in the cellular context cannot be predicted with absolute accuracy [23]Fu Y, Foden JA, Khayter C, et al. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013; 31, 822–826..

Random insertion of HDR templates

In case of KI experiments with HDRT-containing donor plasmids, the donor can insert by NHEJ into genomic regions having random DSBs, as well as integrate into any OFF-target-created DSB [22]Teboul L, Herault Y, Wells S, Qasim W, Pavlovic G. Variability in genome editing outcomes: challenges for research reproducibility and clinical safety. Mol. Ther. 2020; 6, 1422–1431.. The overall frequency of OFF-target DSBs is determined mostly by the specificity of the sgRNA but can also be influenced by the HDRT architecture and the cellular environment.

ON-target HDR template rearrangements

Complex ON-target HDRT rearrangements have been reported, with MMEJ-driven repair based on micro-repeats in dsDNA donor templates as likely mechanism of action. Additionally, complex vector insertions mediated not only by MMEJ but also by NHEJ and HDR have been detected in almost 20% of clones analysed [24]Higashitani Y, Horie K. Long-read sequence analysis of MMEJ-mediated CRISPR genome editing reveals complex on-target vector insertions that may escape standard PCR-based quality control. Sci. Rep. 2023; 13, 11652.. Potential HDRT ON-target rearrangements are not easy to detect by simple PCR-based screens and need to be factored in as possibilities in the detailed QC of clonal lines.

Larger insertions

Unintended larger insertions after nuclease-generated DSB have been uncovered in recent systematic analyses. Insertions mainly consisted of retro-transposable elements, host genomic coding and regulatory sequences and can occur at an allelic frequency of 0.7% [25]Bi C, Yuan B, Zhang Y, Wang M, Tian Y, Li M. Prevalent integration of genomic repetitive and regulatory elements and donor sequences at CRISPR-Cas9-induced breaks. Commun. Biol. 2025; 8, 94.. When double stranded HDRTs are used for the edit, concatemerized or tandem integrated repair templates are among unwanted larger insertions [26]Boroviak K, Fu B, Yang F, Doe B, Bradley A. Revealing hidden complexities of genomic rearrangements generated with Cas9. Sci. Rep. 2017; 7, 12867.. ON-target rearrangements have been described in zygotes and cell lines, especially when using more than one sgRNA in the editing strategy. Dual or multi-guide strategies can trigger rearrangements ranging from inversions, tandem insertions, head-to-tail insertions and duplications in combination with larger deletions [27]Skryabin BV, Kummerfeld DM, Gubar L, et al. Pervasive head-to-tail insertions of DNA templates mask desired CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing events. Sci. Adv. 2020; 6, eaax2941. [28]Blayney J, Foster EM, Jagielowicz M, et al. Unexpectedly high levels of inverted re-insertions using paired sgRNAs for genomic deletions. Methods Protoc. 2020; 3, 53.. HDRT concatemerization and backbone insertion was observed using adeno-associated virus vectors as HDRTs in the generation of transgenic animals [29]Luqman MW, Jenjaroenpun P, Spathos J, et al. Long read sequencing reveals transgene concatemerization and vector sequences integration following AAV-driven electroporation of CRISPR RNP complexes in mouse zygotes. Front. Genome Ed. 2025; 7, 1582097..

Larger deletions

Error-prone repair of nuclease induced DSBs can drive generation of larger ON- and OFF-target deletions. A thorough characterization of indel spectra after CRISPR editing in mouse zygotes detected deletion spectra of up to 600 bp and identified asymmetric deletions using single sgRNAs [30]Shin HY, Wang C, Lee HK, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 targeting events cause complex deletions and insertions at 17 sites in the mouse genome. Nat. Commun. 2017; 8, 15464.. Also, larger deletions can be triggered by surrounding microhomologies, which should be considered in an ON-target context dependent manner [31]Owens DDG, Caulder A, Frontera V, et al. Microhomologies are prevalent at Cas9-induced larger deletions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47, 7402–7417.. A comprehensive analysis of unintended chromosomal modifications in primary hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells reports that large deletions occur in higher frequency at all selected and investigated ON-target sites [32]Park SH, Cao M, Pan Y, et al. Comprehensive analysis and accurate quantification of unintended large gene modifications induced by CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. Sci. Adv. 2022; 8, eabo7676.. Truncation of one of the ends of a DSB during repair was reported to yield >100kb deletions in mouse zygotes [33]Korablev A, Lukyanchikova V, Serova I, Battulin N. On-target CRISPR/Cas9 activity can cause undesigned large deletion in mouse zygotes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020; 21, 3604.. Additionally, deleterious ON-target effects and larger mono-allelic deletions via HDR or NHEJ were reported to happen in up to 40% of gene-edited hiPSC lines [34]Weisheit I, Kroeger JA, Malik R, et al. Detection of deleterious on-target effects after HDR-mediated CRISPR editing. Cell Rep. 2020; 31, 107689., however, the range most likely is line- and edit-specific. Here it is important to note that larger deletions are inherently difficult to identify in simple primary PCR screens since they are usually linked to loss of primer or probe binding sites.

Chromosomal rearrangements

Large chromosomal aberrations triggered by nuclease mediated genome engineering are rare, but when observed, the spectrum can cover deletions, duplications, inversions, balanced or unbalanced reciprocal as well as nonreciprocal translocations [35]Zhang F, Carvalho CMB, Lupski JR. Complex human chromosomal and genomic rearrangements. Trends Genet. 2009; 25, 298–307.. Gene editing of targets close to telomeres has been associated with arm truncation and loss of heterozygosity [36]Przewrocka J, Rowan A, Rosenthal R, Kanu N, Swanton C. Unintended on-target chromosomal instability following CRISPR/Cas9 single gene targeting. Ann. Oncol. 2020; 31, 1270–1273. [37]Boutin J, Rosier J, Cappellen D, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 globin editing can induce megabase-scale copy-neutral losses of heterozygosity in hematopoietic cells. Nat. Commun. 2021; 12, 4922.. Engineering pipelines using more than one guide (and studies affected by pseudogene-based multi-targeting) report megabase rearrangements and multi-lesion alleles [38]Wrona D, Pastukhov O, Pritchard RS, et al. CRISPR-directed therapeutic correction at the NCF1 locus is challenged by frequent incidence of chromosomal deletions. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020; 17, 936–943. [39]Kosicki M, Tomberg K, Bradley A. Repair of double-strand breaks induced by CRISPR-Cas9 leads to large deletions and complex rearrangements. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018; 36, 765–771.. In a CRISPR screen to address the effects of sgRNAs on primary T cell genetic integrity and comparing single guide/template conditions with conditions using multiple guides, both approaches resulted in the observation of chromosomal deletions [40]Tsuchida CA, Brandes N, Bueno R, et al. Mitigation of chromosome loss in clinical CRISPR-Cas9-engineered T cells. Cell 2023; 186, 4567–4582.e20.. Supporting this, genome engineering approaches using one sgRNA without intentional secondary targeting purpose also report chromosomal truncations [41]Cullot G, Boutin J, Toutain J, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing induces megabase-scale chromosomal truncations. Nat. Commun. 2019; 10, 1136.. A recent study employing improved high-sensitivity screening uncovered previously undetected levels of chromosomal translocations in the range between 0.15 and 1.5% [42]Bestas B, Wimberger S, Degtev D, et al. A Type II-B Cas9 nuclease with minimized off-targets and reduced chromosomal translocations in vivo.Nat. Commun. 2023; 14., and use of single cell genomic DNA sequencing techniques confirmed above findings describing unique OFF-editing patterns in single clones [43]Kalter N, Gulati S, Rosenberg M, et al. Precise measurement of CRISPR genome editing outcomes through single-cell DNA sequencing. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2025; 33, 101449.. Those results highlight the potential for unwanted aberrations following gene-editing and stress the importance to thoroughly characterize isolated edited clonal lines.

Regulatory guidelines

The EMA and the US FDA have released recommendations concerning the use of highly expanded allogeneic PSC-derived products for cell therapy [44]European Medicines Agency. Guideline on Safety and Efficacy Follow-up and Risk Management of Advanced Cell Therapy Medicinal Products. Feb 1, 2018. [45]US Food and Drug Administration. Safety Testing of Human Allogeneic Cells Expanded for Use In Cell-Based Medical Products. Apr 2024; FDA. . An EMA guideline on the risk-based approach for evaluation of ATMPs is in place. The key point is to exclude cells that have acquired unwanted mutations or growth-advantageous chromosomal aberrations during the editing process from becoming therapeutic material [46]Madrid M, Lakshkmipathy U, Zhang X, et al. Considerations for the development of iPSC-derived cell therapies: a review of key challenges by the JSRM-ISCT iPSC Committee. Cytotherapy 2024; 26, 1382–1399..

FDA recommendations particularly recommend the use of whole genome sequencing with more than 50× coverage as a method of choice. ‘Justification should be provided for the sequencing method, read depth, and for conclusions related to the safety of the product’[45]US Food and Drug Administration. Safety Testing of Human Allogeneic Cells Expanded for Use In Cell-Based Medical Products. Apr 2024; FDA. . Results need to be analyzed by cross-comparison to databases that reference proto-oncogenes and cancer-associated mutations (such as K-Ras, c-MYC, Tp53, BRCA). Recommendations also cover identification of ON- and OFF-target genome editing and cytogenetic testing with defined acceptance criteria. Validation using orthogonal methodologies is considered best practice. The genetic integrity testing strategies outlined in the following sections take those recommendations into consideration. Additionally, we discuss recent assay developments that are currently not included in the official guidelines but might have the potential to add important extra information in the future.

Genetic integrity testing

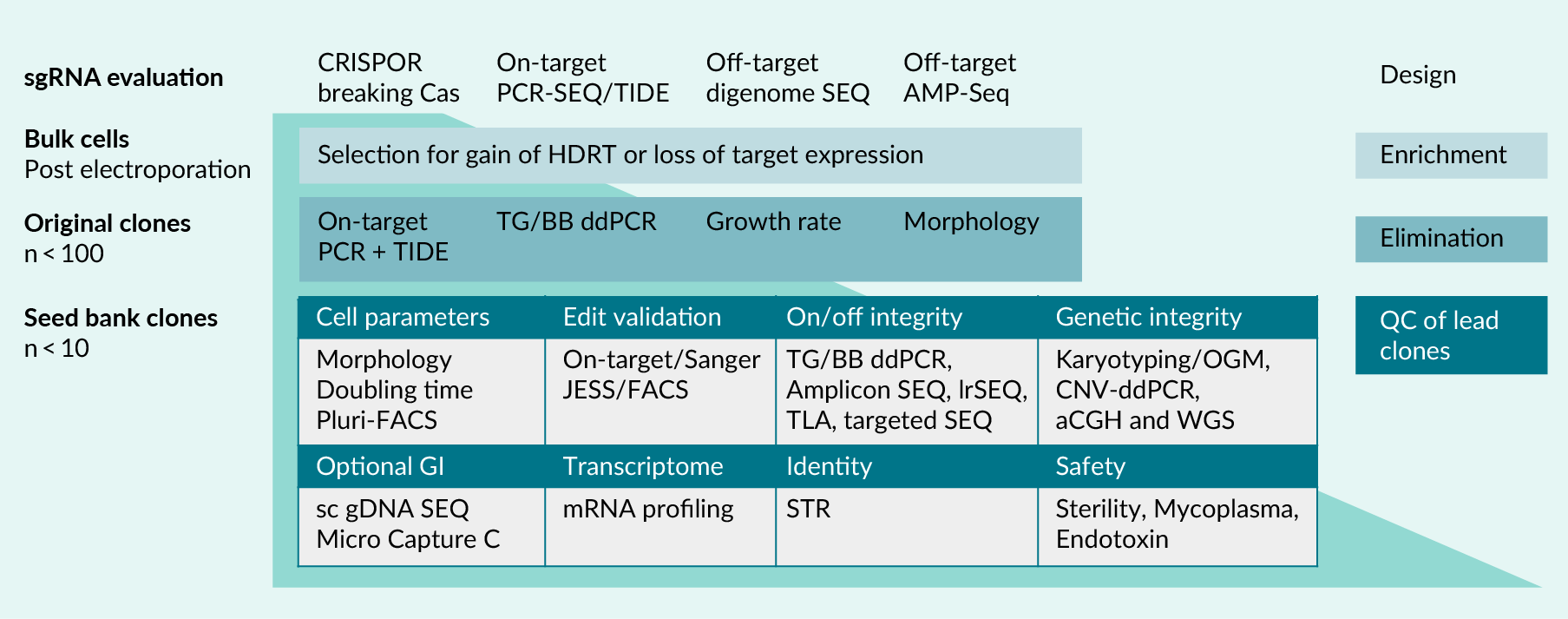

An ATMP must be accompanied by comprehensive genetic integrity testing panels that can uncover critical point mutations and genetic aberrations that might have emerged in the establishment of genome engineered PSC clonal lines, and that may pose a significant risk to patient safety. The screening pipeline ideally directly starts at the initial design phase, in which safe design of reagents as well as experimental evaluation of potential sgRNA mediated OFF-targeting is established for downstream use (Figure 2, ‘Design’ phase). A second level will ideally allow enrichment of gene-edited bulk cells, already ensuring expression of the introduced transgene, or proving absence of gene expression in case of a targeted KO (Figure 2, ‘Enrichment’phase, light green).

A third level can be added at an early, potentially in-process stage. When many clonal lines are generated, a pre-screen procedure can help reducing clone numbers at an early level of the process. Such a pre-screen must be robust and provide clear decision criteria to be able to a priori discard clonal lines (‘elimination phase’). Several aspects can be screened, ranging from cell morphology and pluripotency marker expression, cell division kinetics, ON-target editing up to copy counting of HDRTs and remnant plasmid DNA backbones (Figure 2,‘Elimination’phase, green). The time-consuming full-integrity test ideally is performed once seed banks of pre-selected clones have been safely frozen (Figure 2, ‘QC of lead clones’ phase, dark green). Once best clonal lines are identified and validated, release and safety assays need to be performed. It is important to stress that only safest-possible starting material can be used for downstream differentiation and manufacturing procedures. At every stage, regulatory guidelines and rigorous scientific judgement must be applied to ensure maximum patient safety.

| Figure 2. Suggested schematic representation of validation pipeline for cell therapy medicinal products. |

|---|

|

| (Top) The design phase sets the stage before any cell engineering can start. sgRNAs are designed to best possible bioinformatic evaluation, tested in target cells for ON-target activity and potential OFF-targeting events are assessed and documented. (Middle, light blue): This affects only HDR experiments, in which a potential selection marker can be used for enrichment of gene-edited cell pools. (Middle, darker blue): It is important to have a quick and reliable downgrading procedure from isolated primary clonal lines. ON-target assays, HDRT copy counting, screen for ON-target versus potential OFF-target integration and cell-based assays are applied. (Bottom, table): full QC is performed at frozen seed bank status. All potential pitfalls as discussed in this article are addressed according to regulatory authority guidelines. aCGH: arrayed comparative genome hybridization. AMP-Seq: targeted amplicon sequencing platform. BB: backbone. ddPCR: digital droplet PCR. FACS: fluorescence activated cell sorting. HDRT: homology directed repair template. JESS: automated Western blot system. lrSEQ: whole genome long read sequencing. OGM: optical genome mapping. sc gDNA SEQ: single cell genomic DNA sequencing. STR: short tandem repeat analyses. TG: Transgene. TIDE: tracking of indels by decomposition. TLA: targeted locus amplification. WGS: whole genome short read sequencing. |

Methodologies for genetic integrity & quality assurance

Genome engineering processes deliver bulk cells that, in best-case, can be enriched for presence of the desired edit (in case of KI) or by absence of expression of targeted endogenous genes (in case of KO). Clones are isolated, triaged, and full genetic integrity testing is performed at frozen seed bank stage. Many powerful technologies have been established to address individual questions concerning potential erroneous editing outcomes. We are discussing current methodologies and address the following questions: ‘What can be detected with which methodology’, ‘Where are limitations of the approaches’, ‘Where is room and applicability for orthogonal approaches’, and ‘Which selected combination of assays could deliver the most comprehensive evaluation in an efficient manner’.We address different levels of genetic integrity testing in the following paragraphs, schematically summarized in Table 1.

| Table 1. QC panel for gene-edited PSC products during establishment and screening of clonal lines. | |||||

Step | Evaluation | QC | Limitations | Alternative | Comment |

Cell | Cells fit for purpose | Morphology; doubling time; pluripotency | No validation |

| In process QC |

Edit validation | ON-target editing | PCR and Sanger (KO and KI); WGS; TLA | Complicated multi-allele insertions cannot easily be resolved |

| HDR more complicated |

| TG expression | FACS; qRT-PCR | TG expression or absence of target expression required | JESS/ICC | PoC differentiation as functional proof |

ON integrity | HDRT rearrangement | Amplicon Seq; WGS, lrSEQ | Large amplicons; tandem insertions difficult to resolve; resolution | TLA; Hi-C | WGS as ultimate proof |

OFF targeting | HDRT copy number | TG/BB ddPCR, PCR-SEQ; WGS; lrSEQ | Resolution and HDRT integrity assembly | TLA | WGS as ultimate proof |

| Small indels | WGS; targeted sequencing (TS); StemSeq | Sequencing depth of 50× in WGS; analytical pipeline | TS >10k coverage; StemSeq panel | Orthogonal QC required |

Genetic integrity | Duplications | Karyotyping; WGS; lrSEQ | Low resolution | Hi-C; OGM |

|

Inversions | WGS; lrSEQ | Difficult detection by WGS | Hi-C |

| |

| Large deletions | WGS; lrSEQ; aCGH |

| Hi-C |

|

| Large Insertions | WGS; lrSEQ; aCGH |

| Hi-C |

|

| Loss of chromosome arms | CNV-ddPCR; Karyotyping; lrSEQ | Selected regions only; low resolution | Hi-C; OGM |

|

| Translocations | Karyotyping; WGS; lrSEQ | Balanced, unbalanced, non- and reciprocal hard to detect | Hi-C; OGM | Specialized pipeline needed |

Transcriptome | Fitness post edit | Microarray |

|

| Not mandatory |

Identity/safety | Release of validated material | STR, MP, sterility, endotoxin |

|

| Part of release |

General cell fitness is monitored as an in-process control. Doubling time and cell morphology are initial indicators for proper PSC behaviour, the Evotec proprietary Pluri-FACS ensures expression of all relevant pluripotency marker. ON-target edit is validated initially by ON-target PCR with Sanger sequencing accompanied by ddPCR HDRT copy counting. Detailed clonal testing (darker blue section) comprises evaluation of ON-target integrity, ruling out deleterious OFF-target effects and ensuring full genetic integrity. Transcriptome analyses are optional and can be used to corroborate other results. Release assays concern questions on cellular identity and sterility. All potential pitfalls are addressed in the accompanying text according to regulatory authority guidelines. aCGH: arrayed comparative genome hybridization. BB: backbone. ddPCR: digital droplet PCR. HDR: homology directed repair. HDRT: HDR template. Hi-C: micro C proximity capture for detection of chromosome interactions. ICC: immunocytochemistry. JESS: automated Western blot system. KI: knock in. KO: knock out. lrSEQ: whole genome long-read sequencing. MP: mycoplasma testing. OGM: optical genome mapping. PoC: proof of concept. QC: quality control. STR: short tandem repeat analyses. TG: transgene. TLA: targeted locus amplification. TS: targeted sequencing. WGS: short read whole genome sequencing. | |||||

Cellular fitness and pluripotency

Morphology assessment of PSC cultures requires expert supervision and is hard to automate. However, for a trained team, cell morphology rapidly and with essentially no cost provides information about unwanted spontaneous differentiation in cultured cells. Differentiated clones with spindle-like cells and undefined edges should generally be discarded. Verification of expression of key pluripotency markers by validated flow cytometry to >98–99% is an important measure to demonstrate and ensure cell pluripotency. Monitoring of maintained pluripotency level is a constant assay to be repeated in regular intervals during editing and during routine maintenance cell culture.

ON-target edit validation

The first step in ON-target validation is typically performed by a locus specific PCR. The logic of the assay differs between screening for KO or for precise integration of HDRTs (KI). Validation of a KO involves PCR amplification of the target site. The amplicon size can already reveal presence or absence of larger indels. Determination of biallelic vs. monoallelic KO as well as the nature of the indels can be analysed using the TIDE algorithm [47]Brinkman E, Chen T, Amendola M, van Steensel B. Easy quantitative assessment of genome editing by sequence trace decomposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42, e168.. TIDE can estimate indel classes in a population average but cannot unequivocally identify mono- vs. biallelic homozygous events. Results can be either substantiated by subcloning of amplicons with subsequent clonal sequencing, or zygosity at the ON-target locus can be confirmed with targeted amplicon deep-sequencing (ideally with >1000x fold coverage). As a caveat, the initial PCR-based detection of only one allele can be caused by either predominant MMEJ repair outcomes (resulting in the biallelic same indel) or could result from a larger-than-expected deletion that removed one of the primer binding sites, potentially masking the actual genotype [31]Owens DDG, Caulder A, Frontera V, et al. Microhomologies are prevalent at Cas9-induced larger deletions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47, 7402–7417.. Amplification of larger ON-target fragments has the potential to resolve this issue, but ultimately joint efforts of short- and long-read WGS can confirm the allelic status of the ON-target event.

Confirmation of ON-target insertion (KI) can use external/internal PCRs for both arms of the HDRT to ensure 5´ and 3´ site-specific integration. Presence of both expected amplicon sizes is indicative for proper insertion, which on top can be confirmed by amplicon Sanger sequencing. This initial screen should be accompanied by a PCR to amplify the remaining, non-HDRed allele as proof of the allelic status. If the WT allele can be amplified, sequencing will determine the indel and confirms monoallelic HDR. If amplification fails, this can be indicative of either bi-allelic HDR or of a larger ON-target deletion. In this context, full HDRT integrity and allelic status will be further validated using complementary methods (e.g. long read sequencing as detailed below).

For KI validation, expression of the payload, or for KO, absence of expression of the target gene, can be analysed on protein level using immune assays (flow cytometry, JESS, ICC, IHC), given availability of target antibodies. Any applicable immune assay can give an important functional readout and is already possible at early stages. Protein data can uncover expression strength in PSCs, can reveal functional protein trafficking and can validate correct subcellular localization.

ON-target HDRT integrity assessment

This paragraph is applicable only to HDR events, where transgene cassettes need to be precisely repaired into the genome. When analysing homology directed repair outcomes, a ddPCR assay can detect payload copy numbers (TG, transgene assay) as well as remnant plasmid DNA (BB, backbone assay, which would be indicative of random insertion events). Additionally, target specific ddPCR assays can be used to investigate the overall structure of the HDRT. Primers and probes can be designed to detect potential boundaries of head-to-tail or tail-to-head concatemeric insertions, which are generally undetectable by simple ON-target PCR screening. If short homology arms are used or if NHEJ based insertion mechanisms are employed, junction ddPCR assays can help determining precise HDRT insertions. Also, tiling ddPCR across the entire length of the HDRT can be applied to map potential truncations or rearrangements, however, a follow up with base-pair resolution is highly recommended for final validation (e.g. by one or several of the below listed assays).

HDRT ddPCR can uncover potential multi-copy integrations (in concert with the ON-target PCR screen). Having a fast turnaround time, the assay allows de-selection of clones during the initial clonal selection phase, with TG copy numbers exceeding 2 or with any detectable backbone plasmid being indicative of random genomic insertions. As examples for HDRT based ddPCR, TG n=1 can result from proper monoallelic targeting (in combination with ON-target PCR results. TG n=2 could be either a biallelic targeting, a monoallelic ON-target event combined with a single copy random insertion or by a concatemerized insertion (all result need correlation with HDRT and remaining WT allele ON-target PCRs). TG n>3 is a clear identifier that at least one copy of the HDRT has been randomly or erroneously inserted or episomal plasmid DNA is unexpectedly maintained after prolonged culture after editing and clonal isolation. The HDRT assay does not give information on overall HDRT-integrity and is applicable only for clonal populations, however, clear advantages of this assay lie in its easy quantification and its short turnaround time. Combined transgene and backbone ddPCR assays (in correlation with ON-target PCR assays) establish a robust foundation for subsequent analyses and have the potential to eliminate improperly edited clonal lines as a robust pre-screening effort as discussed above.

ON-target long-range amplicon sequencing (i.e. PCR over the entire integration site using primers placed outside the HDRT sequence, and analysis of the amplicon via NGS) is a useful process-development tool and can even work in bulk populations. Although potentially cumbersome to establish and custom for each locus and HDRT, the assay has the potential to be validated for ON-target integrity assessment. As a beneficial side effect, tandem or multi-copy ON-site insertions would naturally impede amplification due to the larger payload and would produce a non-amplification, in which case aberrant clones would be automatically eliminated.

Long-read whole genome sequencing (lrSEQ) with sufficient coverage has the potential to identify HDRT rearrangements (deletions, translocations, tandem insertions, inversions) and can detect general HDRT OFF-target insertions. Since lrSEQ generally delivers a shallow read depth, interpretation of bulk results, in which ON-target editing happens in less than 1–5% of total cells, is impaired by the low coverage. lrSEQ, however, is very well suited for clonal populations with defined mono- or biallelic insertions. The read-depth of current lrSEQ does not allow precise base-calling, nevertheless, lrSEQ can reliably uncover structural HDRT aberrations. A simple approach with 5× coverage will suffice as a primary screening methodology. For reliable detection of structural aberrations using currently available platforms (e.g. Oxford Nanopore or PacBio HiFi), a >15–20× coverage for clonal lines when screening for structural variations, and a >30× coverage when aiming to detect larger structural and smaller variants at high precision is recommended. lrSEQ data can give a comprehensive overview not only on HDRT integrity but also on larger chromosomal rearrangements (see below). To corroborate the findings, lrSEQ ideally is combined with assays providing higher resolution (e.g. short read WGS or targeted sequencing assays), combining their analytic powers.

Alternatively, targeted locus amplification (TLA) is a proximity ligation-based assay with NGS evaluation. It can uncover payload integrity ON-target and, in the same run, can identify OFF-targeting of additional copy insertions with their precise location [48]de Vree P, de Wit E, Yilmaz M, et al. Targeted sequencing by proximity ligation for comprehensive variant detection and local haplotyping. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014; 32, 1019–1025.. TLA, due to its targeted sequencing approach, however, is naturally biased and therefore usually requires complementation with orthogonal methodologies.

Short read WGS, even while delivering a high coverage and read depth, cannot fully verify HDRT integrity as a stand-alone methodology. HDRT homology arms are usually larger than 500bp and as such short read approaches are inherently not suitable for precise determination of the insertion site. An additional complication can arise from HDRTs containing non-codon-optimized human genes, since those templates generate unmatchable reads. However, once long-read WGS in conjunction with TG ddPCR and ON-target PCR has established a bona fide single copy insertion, WGS validation on a single base resolution can be feasible. As for most integrity testing areas, not a single methodology will give all answers, but when combining several assays with TG expression data and WGS ON-target data, proper HDRT-integrity can be ensured.

Assessment of OFF-target indels

Genome wide short OFF target indels (insertion or deletion of in average less than 10 nucleotides) as a byproduct of genome engineering are the most common deleterious outcome. Analysis of potential harmful mutations is mandatory. Due to genome size and abundance of data that needs to be analysed in sufficient coverage, orthogonal approaches and well-defined analysis pipelines are required.

Genome editing OFF-target indels are typically present in much less than 1% in bulk populations. The generation of an ATMP usually does not end with a bulk population but requires isolation and characterization of clonal lines. The previously mentioned nomination and validation procedure (see paragraph Genetic Engineering of hiPSC) is used for bulk cells but, most importantly, also for isolated clonal lines. Well-selected sgRNAs generate mostly ON-target DSBs, but erroneous OFF-targeting cannot be excluded. Nominated loci can be addressed using targeted high-depth validation to quantify potential OFF-target indels. The amplification method of choice (e.g. using custom amplicon panels such as rhAmpSeq or duplex-UMI amplicon sequencing) is sufficient with 100x coverage per target in clonal populations but should exceed 1000x (preferably 10.000x) coverage to ensure sufficient resolution in bulk populations. Additional targeted approaches using custom designed panels are based on prior knowledge. Targeted sequencing is the most sensitive detection assay for rare OFF targets concerning indels, SNPs, CNVs affecting known risk loci associated with frequent aberrations in PSCs [49]Lezmi E, Jung J, Benvenisty N. High prevalence of acquired cancer-related mutations in 146 human pluripotent stem cell lines and their differentiated derivatives. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024; 42, 1667–1671.. Targeted amplification, however, should best be combined with unbiased NGS approaches. As recommended by the FDA (Safety Testing of Human Allogeneic Cells Expanded for Use in Cell-Based Medical Products), in particular screening for mutations in the p53 pathway post genome engineering [50]Haapaniemi E, Botla S, Persson J, Schmierer B, Taipale J. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing induces a p53-mediated DNA damage response. Nat. Med. 2018; 24, 927–930. should be an integral part. It is important to stress that all above-mentioned targeted panels are site-limited and should be paired with unbiased WGS as an orthogonal method.

WGS at >50× coverage is considered the gold standard recommended by regulatory authorities. It is important to define which strategies will be applied for the evaluation and assessment of CNVs, indels and SNPs. Analyses require comparison to a public database reference genome, creating a donor-specific (an option in the case of iPSCs) or cell-line-specific baseline genome which can serve as starting point for all analyses of subsequent gene edits. Any new WGS-build at different steps of cell culture and cloning can be co-referenced for genetic integrity monitoring over time. The analysis pipeline should investigate well-curated lists of genes and variants with impact on the fitness of the edited clone. Those lists can contain genes from relevant pathways, lineage specific genes, oncogenes and tumour suppressors, genes affecting PSC pluripotency, as well as ClinVAR/COSMIC/OMIM disease-relevant variants. A defined strategy (following EMA recommendations) is required for interpretation of short WGS reads to have enable decisions based on pre-defined criteria and arguments on the use of the final selected clone, requiring expert review of the results. This is a labour-intensive approach, however, delivers highest coverage of most genetic aberrations that can occur. In a best possible scenario, a fully annotated new genome build is assembled for the clone selected for manufacturing. Importantly, assembly of repeat structures, tandem insertions, unbalanced and balanced translocations or reciprocal translocations is not always unambiguous since large structural genome variations are not fully covered in the process of classical short read NGS (see section on genetic integrity and stability below). Further methodologies (as outlined in the sections below) need to be considered to have a comprehensive understanding of the overall genetic integrity of the derived clonal lines. It is important to stress that short-read WGS at this sequencing depth can provide sensitive discovery of low-frequency OFF-targeting events only in clonal but rather not in bulk populations.

Genetic integrity and stability

ddPCR services to detect CNVs commonly observed in PSCs are commercially available. Custom probes typically cover about 20 published known high frequency chromosomal breakpoints in PSCs [51]Assou S, Girault N, Plinet M et al. Recurrent genetic abnormalities in human pluripotent stem cells: definition and routine detection in culture supernatant by targeted droplet digital PCR. Stem Cell Rep. 2020; 14, 1–8.. This type of selective assay is relatively cheap and has a fast turnaround time. While it cannot be used as a stand-alone genetic integrity assay due to the limited range of targets, it nevertheless is a useful tool for pre-exclusion screening whose results need to be later substantiated by other methods.

One methodology suggested by the FDA for analysis of global rearrangements is karyotyping by G-banding [52]Yunis JJ, Sanchez O. G-banding and chromosome structure. Chromosoma 1973; 44, 15–23., with at least 40 metaphase spreads to gain statistical significance. G-banding is an established assay, and certified clinical diagnostic service providers are available. Polyploidies, duplications, large deletions and larger translocations can be identified, potentially even larger inversions. Disadvantages of the methodology are mostly the limit of its statistical power due to low sample numbers, as well as a poor detection potential for smaller rearrangements. A technical improvement in this area could come from optical genome mapping (OGM) [53]Villarejo LG, Gerding WM, Bachmann L, et al. Optical genome mapping reveals genomic alterations upon gene editing in hiPSCs: implications for neural tissue differentiation and brain organoid research. Cells 2024; 13, 507.. Herein, high molecular weight DNA is stained with intercalating dyes and subjected to imaging on chip-nanochannel arrays. Changes in the patterning in comparison to a reference genome reflect copy number and structural anomalies, including detection of balanced translocations. This is a recently developed technology, and future research needs to demonstrate its full range of applicability.

lrSEQ can give a wholistic overview about most common larger chromosomal aberrations and at the same time informs about HDRT copy numbers and about general integrity of the HDRT ON-target. With a typical read depth <5–10 and with higher per-base error rates, it cannot reliably deliver SNV calls and should be confirmed by higher coverage methodologies. Importantly, however, bioinformatic assembly of the average 10kb long-read fragments allows assembly of the co-linear sequence of larger fragments, especially for larger HDRTs. WGS can ensure trustworthy sequence information, however, in turn has only limited capability in calling rearrangements (as discussed above). Potential caveats could come from biallelic modification of the same target, where precise calling might be impossible. Therefore, combined long- and short-read WGS to date seems the best methodology for verifying HDRT integrity, and for detection of most potential genetic aberrations that can be accounted for.

Arrayed comparative genome hybridization (aCGH) is an orthogonal approach to WGS with a lower resolution, but capable to detect larger insertions or deletions [54]Pinkel D, Segraves R, Sudar D, et al. High-resolution analysis of DNA copy number variation using comparative genomic hybridization to microarrays. Nat. Genet. 1998; 20, 207–211.. Comparative hybridization with differentially labelled fluorescent probes results in equal, over- or under-representation in the test sample and indicates genomic aberrations that can be mapped according to the probe sets, which are placed at regular intervals along the genome. aCGH is a genome-wide, unbiased assay that several approved clinical laboratories can provide, comes at a relatively low cost and with a relatively fast turnaround time. Limitations of the assay is resolution (standard assays have a 50kb lower limit) is that CNVs can only be uncovered in regions where probes are hybridizing, and that no information can be obtained at the SNP level. As such, aCGH can be considered a robust first test, giving an idea of the overall genetic integrity post edit, however, should be accompanied with deeper coverage methodologies.

Two recently developed methodologies have the potential to add additional information into the genetic integrity evaluation pipeline. Tapestri single cell genomic DNA sequencing is a technology designed for in-depth analysis of editing outcomes that aims to allow simultaneous sequencing of several 100 loci in up to 20k of single cells, adding a high level of resolution [43]Kalter N, Gulati S, Rosenberg M, et al. Precise measurement of CRISPR genome editing outcomes through single-cell DNA sequencing. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2025; 33, 101449.. Tapestri uses custom defined panels with high sensitivity, potentially most orthologous to targeted sequencing panels, however, with single cell output. Its key strength could lie in the evaluation of bulk editing outcomes and could also be used for confirmation of genetic integrity in isolated clonal lines. It is a custom approach with a limited target size and does not give full genome coverage, however, in combination with non-biased WGS could be a useful tool, especially for process development purposes.

Micro capture C [55]Hamley JC, Li H, Denny N, Downes D, Davies JOJ. Determining chromatin architecture with Micro Capture-C. Nat. Protoc. 2023; 18, 1687–1711.Hamley JC, Li H, Denny N, Downes D, Davies JOJ. Determining chromatin architecture with Micro Capture-C. Nat. Protoc. 2023; 18, 1687–1711. [56]Lieberman-Aiden E, van Berkum NL, Williams L, et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 2009; 326, 289–293. is a cross-linking positional approach evaluated by NGS. DNA fragments next to each other within cell nuclei are cross-linked, and co-linear as well as rearranged interactions can be revealed using a proximity interaction matrix, similar to the establishment of 3D chromosome interaction matrices [55]Hamley JC, Li H, Denny N, Downes D, Davies JOJ. Determining chromatin architecture with Micro Capture-C. Nat. Protoc. 2023; 18, 1687–1711.. The principle of the methodology is analogous to TLA; however, it is unbiased, not payload-centred and covers the whole genome. The methodology has the potential to reveal breakpoints, inversions, translocations, fusions, duplications, tandem inversions, smaller and larger deletions all in one in one assay, all depending on the sequencing depth [57]Fang H, Eacker SM, Wu Y, et al. Genetic and functional characterization of inherited complex chromosomal rearrangements in a family with multisystem anomalies. Genet. Med. Open 2025; 3, 103423.. Being a very recent technology development, future research needs to demonstrate how reliably Micro capture C or similar adaptations can complement or potentially even surpass the previously described combinations of genetic integrity testing approaches.

Transcriptome effects

Transcriptome analyses are indirectly assessing genetic integrity, however, can reveal insights into perturbations that potentially could be undetectable using above listed methodologies. This assay can uncover changes in preference of isoform expression as well as altered lncRNA or miRNA profiles. It is an inherently unbiased approach and has the potential to add a different viewpoint on global changes resulting from aberrant genome engineering.

Cell identity

Cell identity determination is a mandatory release assay. Short tandem repeats (STRs) are short repetitive DNA repeats that are used to classify the origin of the cell line and are detected by a PCR-based length polymorphism. STR profiling is used to validate origin of cells [58]Yoon JG, Lee S, Cho J, et al. Diagnostic uplift through the implementation of short tandem repeat analysis using exome sequencing. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2024; 32, 584–587.. Several clinically accredited providers are available.

Safety and release assays beyond genetic integrity and identity testing

Mandatory safety and release assays include sterility tests, mycoplasma testing, endotoxin release testing, adventitious agents and viral safety testing, and absence of genome engineering reagents post edit in the final medicinal product.

Translational implications

Genetic integrity monitoring is a fundamental aspect when producing ATMPs. PSCs are an ideal starting point for allogeneic cell therapies, but long-term culture has shown to predispose cells to acquisition of genetic alterations. Continuous monitoring of genetic integrity is key during routine maintenance, expansion and banking, but is equally important during and after genetic engineering. Based on rigid assessment of potential aberrations and on detailed analysis of the coverage potential and inherent gaps of available testing methods, a comprehensive testing portfolio needs to be in place to cover both, general and editing-related risks.

We summarized potential ‘mishaps’ that occur during genetic engineering of cells and have presented a variety of different analytical assays to address significant issues. Not all types of events necessarily occur in the same cell, in the same cell line or even at the same time, however, knowing what can potentially go wrong raises awareness which points to address with relevant genetic integrity testing assays. For long term culture and post genome edit, as previously discussed [14]Zanella F, Narcu R. Genetic stability of hPSCs and considerations for cell therapy. Cell & Gene Therapy Insights 2024; 10, 159–170., not a single assay can cover all potential genetic rearrangements. A thoughtful combination of different assays is required to gain access to the full picture. We would like to highlight two scenarios that are particularly important in the generation of genome-edited PSCs and present two possible minimalistic assay scenarios (Table 2).

When genetically engineering a loss-of-function allele (Table 2 upper part: KO), an ON-target edit can be confirmed by PCR amplification of the edit area with subsequent Sanger sequencing. Indel composition in both alleles can be determined by TIDE, and only biallelic out-of-frame mutations are considered successful KO edit outcomes. Short range WGS can assess any engineering-based off-targeting, preferably supported by targeted sequencing informed by initial sgRNA pre-evaluation. General genetic integrity can be validated using a panel of orthogonal assays as discussed in the sections above.

When aiming to validate a gain of function allele (Table 2 lower part: KI), initial ON-target integration can be validated by outside-in and inside-out PCRs to validate proper HDR of both arms of the donor. The PCR spanning the unedited WT locus serves as conformation of the allelic status. TG and (artefactual plasmid DNA remnant) BB ddPCR copy counting, in correlation with the ON-target PCR, can inform on potential mono- or biallelic HDR. Likewise, the same assay can also uncover potential random insertion events (BB > 0 and TG > 2). Whole genome long range sequencing can be applied to validate ON-target HDRT integrity and to support TG ddPCR results on total copy counting. Additionally, lrSEQ will give an overview on general genetic integrity. Absence of ON-target inversions, deletions or tandem insertions can help selecting clones for subsequent complimentary short read WGS, with which also any indels accidentally caused by the editing procedure can be identified. If single-copy ON-site HDRT integration can be assured, WGS can inform on HDRT integrity on the base-pair level as well as confirm the allelic ON-target status. Indel prevalence as well as genetic integrity of cells can be further addressed by targeted sequencing.

Table 2. Minimal QC procedures for KO and KI lines. | |||

| Step | Assay | Purpose |

KO | 1 | ON-target PCR | Validation of biallelic KO |

| 2 | Targeted sequencing | Assessment of engineering-based OFF-targeting |

| 3 | WGS; lrSEQ; aCGH; CNV-ddPCR; Karyotyping | General genetic integrity |

KI | 1 | ON-target PCR | Validation of correct 5´ and 3´ HDRT integration |

| 2 | ON-target WT PCR | Allelic discrimination |

| 3 | TG ddPCR copy count | n=1: ON-target PCR OK → indicative of monoallelic targeting n=2: ON-target PCR OK/WT PCR positive → potential biallelic targeting n=2: ON-target and WT PCR OK → ON + OFF-target or tandem ON-targeting n>3: irrespective of ON-PCR → random insertion ON or OFF |

| 4 | BB ddPCR copy count | n>0 indicative of random targeting |

| 5 | ON-target lrSEQ | Determination of HDRT integrity Proof of absence of duplications, tandem insertions, inversions, rearrangements which otherwise would be hard to detect by WGS alone |

| 6 | ON-target WGS | Requires proof of absence of ON-target duplications by lrSEQ If TG ddPCR n=2, validation of biallelic or ON-target + random insertion Full sequence confirmation of HDRT |

| 7 | Targeted sequencing | Assessment of engineering-based OFF-targeting |

| 8 | WGS; lrSEQ; aCGH; CNV-ddPCR; Karyotyping | General genetic integrity |

KO: the 3 typical successive steps of validation of the genetic model are depicted. A ‘KO only’ edit is usually not the main ATMP outcome. KI: 8 steps for full validation of ON- and OFF-targeting including HDR integrity are depicted. In both cases, the choice of orthogonal methodologies critically depends on the editing pipeline. aCGH: arrayed comparative genome hybridization. BB: backbone. ddPCR: digital droplet PCR. KO: knock out. lrSEQ: whole genome long-read sequencing. TG: transgene. WGS: short read whole genome sequencing. | |||

Concluding remarks

Diverse editing strategies require different combinatorial sets to uncover potential genetic aberrations that may have occurred as a by-product of the editing procedure. Many independent studies have elucidated individual aberrations with varied frequencies in various cell lines, all analyzing different editing strategies. Ultimately, when generating ATMPs it needs to be ensured on a clonal level that the cell therapy product does not pose a risk. Many different methodologies are available, and their use needs to be adapted to the question of choice. The use of combined long- or short-read WGS data sets seems the currently most appropriate starting point. In line with EMA and FDA recommendations, the evaluation thereof mainly relies on curated gene lists. Any detected de novo mutation requires a science-based decision, and an expert-based de-risking approach. If implemented properly, this can be performed by pre-defined algorithms and lists and applying them in an automated fashion once data become available, thereby eliminating the human factor. In the coding genome, mutations in exons (out of frame or codon changing), mutations that create de novo STOP codons or deleterious missense mutations, that alter splice sites or change regulatory regions are obvious red flags, while effects of SNPs in intergenic and intronic regions usually are less impactful and therefore are typically not applied for ATMP release. Regardless, it is of utmost importance to take all available information on validation of genetic integrity into consideration to ensure the safest-possible starting material for cell therapies.

References

1. Patel KK, Tariveranmoshabad M, Kadu S, Shobaki N, June C. From concept to cure: the evolution of CAR-T cell therapy. Mol. Ther. 2025; 33, 2123–2140. Crossref

2. Schett G, Müller F, Taubmann J, et al. Advancements and challenges in CAR T cell therapy in autoimmune diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2024; 20, 531–544. Crossref

3. Yu J, Thomson JA. Pluripotent stem cell lines. Genes Dev. 2008; 22, 1987–1997. Crossref

4. Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006; 126, 663–676. Crossref

5. Yamanaka S. Pluripotent stem cell-based cell therapy—promise and challenges. Cell Stem Cell 2020; 27, 523–53. Crossref

6. Kirkeby A, Main H, Carpenter M. Pluripotent stem-cell-derived therapies in clinical trial: a 2025 update. Cell Stem Cell 2025; 32, 10–37. Crossref

7. Deuse T, Schrepfer S. Progress and challenges in developing allogeneic cell therapies. Cell Stem Cell. 2025; 32, 513–528. Crossref

8. Paasch D, Meyer J, Stamopoulou A, et al. Ex vivo generation of CAR macrophages from hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells for use in cancer therapy. Cells 2022; 11, 994. Crossref

9. Hu X, Beauchesne P, Wang C, et al. Hypoimmune CD19 CAR T cells evade allorejection in patients with cancer and autoimmune disease. Cell Stem Cell 2025; 32, 1356–1368.e4. Crossref

10. Wang X, Zhang Y, Jin L, et al. An iPSC-derived CD19/BCMA CAR-NK therapy in a patient with systemic sclerosis. Cell 2025; 188, 4225–4238.e12. Crossref

11. Fukutani Y, Kurachi K, Torisawa YS, et al. Human iPSC-derived NK cells armed with CCL19, CCR2B, high-affinity CD16, IL-15, and NKG2D complex enhance anti-solid tumor activity. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025; 16, 373. Crossref

12. Lanza R, Russell DW, Nagy A. Engineering universal cells that evade immune detection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019; 19, 723–733. Crossref

13. Vantyghem MC, de Koning EJP, Pattou F, Rickels MR. Advances in β-cell replacement therapy for the treatment of type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2019; 394, 1274–1285. Crossref

14. Zanella F, Narcu R. Genetic stability of hPSCs and considerations for cell therapy. Cell & Gene Therapy Insights 2024; 10, 159–170. Crossref

15. Pacesa M, Pelea O, Jinek M. Past, present, and future of CRISPR genome editing technologies. Cell 2024; 187, 1076–1100. Crossref

16. Gelot C, Magdalou I, Lopez BS. Replication stress in mammalian cells and its consequences for mitosis. Genes 2015; 6, 267–298. Crossref

17. Haider S, Mussolino C. Fine-tuning homology-directed repair (HDR) for precision genome editing: current strategies and future directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025; 26, 4067. Crossref

18. Liu G, Zhang Y, Zhang T. Computational approaches for effective CRISPR guide RNA design and evaluation. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020; 18, 35–44. Crossref

19. Guo C, Ma X, Gao F, Guo Y. Off-target effects in CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023; 11, 1143157. Crossref

20. Kim D, Kang BC, Kim JS. Identifying genome-wide off-target sites of CRISPR RNA-guided nucleases and deaminases with Digenome-SEQ. Nat. Protoc. 2021; 16, 1170–1192. Crossref

21. Longo GMC, Sayols S, Kotini AG, et al. Linking CRISPR–Cas9 double-strand break profiles to gene editing precision with BreakTag. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024; 43, 608–622. Crossref

22. Teboul L, Herault Y, Wells S, Qasim W, Pavlovic G. Variability in genome editing outcomes: challenges for research reproducibility and clinical safety. Mol. Ther. 2020; 6, 1422–1431. Crossref

23. Fu Y, Foden JA, Khayter C, et al. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013; 31, 822–826. Crossref

24. Higashitani Y, Horie K. Long-read sequence analysis of MMEJ-mediated CRISPR genome editing reveals complex on-target vector insertions that may escape standard PCR-based quality control. Sci. Rep. 2023; 13, 11652. Crossref

25. Bi C, Yuan B, Zhang Y, Wang M, Tian Y, Li M. Prevalent integration of genomic repetitive and regulatory elements and donor sequences at CRISPR-Cas9-induced breaks. Commun. Biol. 2025; 8, 94. Crossref

26. Boroviak K, Fu B, Yang F, Doe B, Bradley A. Revealing hidden complexities of genomic rearrangements generated with Cas9. Sci. Rep. 2017; 7, 12867. Crossref

27. Skryabin BV, Kummerfeld DM, Gubar L, et al. Pervasive head-to-tail insertions of DNA templates mask desired CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing events. Sci. Adv. 2020; 6, eaax2941. Crossref

28. Blayney J, Foster EM, Jagielowicz M, et al. Unexpectedly high levels of inverted re-insertions using paired sgRNAs for genomic deletions. Methods Protoc. 2020; 3, 53. Crossref

29. Luqman MW, Jenjaroenpun P, Spathos J, et al. Long read sequencing reveals transgene concatemerization and vector sequences integration following AAV-driven electroporation of CRISPR RNP complexes in mouse zygotes. Front. Genome Ed. 2025; 7, 1582097. Crossref

30. Shin HY, Wang C, Lee HK, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 targeting events cause complex deletions and insertions at 17 sites in the mouse genome. Nat. Commun. 2017; 8, 15464. Crossref

31. Owens DDG, Caulder A, Frontera V, et al. Microhomologies are prevalent at Cas9-induced larger deletions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47, 7402–7417. Crossref

32. Park SH, Cao M, Pan Y, et al. Comprehensive analysis and accurate quantification of unintended large gene modifications induced by CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. Sci. Adv. 2022; 8, eabo7676. Crossref

33. Korablev A, Lukyanchikova V, Serova I, Battulin N. On-target CRISPR/Cas9 activity can cause undesigned large deletion in mouse zygotes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020; 21, 3604. Crossref

34. Weisheit I, Kroeger JA, Malik R, et al. Detection of deleterious on-target effects after HDR-mediated CRISPR editing. Cell Rep. 2020; 31, 107689. Crossref

35. Zhang F, Carvalho CMB, Lupski JR. Complex human chromosomal and genomic rearrangements. Trends Genet. 2009; 25, 298–307. Crossref

36. Przewrocka J, Rowan A, Rosenthal R, Kanu N, Swanton C. Unintended on-target chromosomal instability following CRISPR/Cas9 single gene targeting. Ann. Oncol. 2020; 31, 1270–1273. Crossref

37. Boutin J, Rosier J, Cappellen D, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 globin editing can induce megabase-scale copy-neutral losses of heterozygosity in hematopoietic cells. Nat. Commun. 2021; 12, 4922. Crossref

38. Wrona D, Pastukhov O, Pritchard RS, et al. CRISPR-directed therapeutic correction at the NCF1 locus is challenged by frequent incidence of chromosomal deletions. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020; 17, 936–943. Crossref

39. Kosicki M, Tomberg K, Bradley A. Repair of double-strand breaks induced by CRISPR-Cas9 leads to large deletions and complex rearrangements. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018; 36, 765–771. Crossref

40. Tsuchida CA, Brandes N, Bueno R, et al. Mitigation of chromosome loss in clinical CRISPR-Cas9-engineered T cells. Cell 2023; 186, 4567–4582.e20. Crossref

41. Cullot G, Boutin J, Toutain J, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing induces megabase-scale chromosomal truncations. Nat. Commun. 2019; 10, 1136. Crossref

42. Bestas B, Wimberger S, Degtev D, et al. A Type II-B Cas9 nuclease with minimized off-targets and reduced chromosomal translocations in vivo.Nat. Commun. 2023; 14. Crossref

43. Kalter N, Gulati S, Rosenberg M, et al. Precise measurement of CRISPR genome editing outcomes through single-cell DNA sequencing. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2025; 33, 101449. Crossref

44. European Medicines Agency. Guideline on Safety and Efficacy Follow-up and Risk Management of Advanced Cell Therapy Medicinal Products. Feb 1, 2018. Link

45. US Food and Drug Administration. Safety Testing of Human Allogeneic Cells Expanded for Use In Cell-Based Medical Products. Apr 2024; FDA. Link

46. Madrid M, Lakshkmipathy U, Zhang X, et al. Considerations for the development of iPSC-derived cell therapies: a review of key challenges by the JSRM-ISCT iPSC Committee. Cytotherapy 2024; 26, 1382–1399. Crossref

47. Brinkman E, Chen T, Amendola M, van Steensel B. Easy quantitative assessment of genome editing by sequence trace decomposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42, e168. Crossref

48. de Vree P, de Wit E, Yilmaz M, et al. Targeted sequencing by proximity ligation for comprehensive variant detection and local haplotyping. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014; 32, 1019–1025. Crossref

49. Lezmi E, Jung J, Benvenisty N. High prevalence of acquired cancer-related mutations in 146 human pluripotent stem cell lines and their differentiated derivatives. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024; 42, 1667–1671. Crossref

50. Haapaniemi E, Botla S, Persson J, Schmierer B, Taipale J. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing induces a p53-mediated DNA damage response. Nat. Med. 2018; 24, 927–930. Crossref

51. Assou S, Girault N, Plinet M et al. Recurrent genetic abnormalities in human pluripotent stem cells: definition and routine detection in culture supernatant by targeted droplet digital PCR. Stem Cell Rep. 2020; 14, 1–8. Crossref

52. Yunis JJ, Sanchez O. G-banding and chromosome structure. Chromosoma 1973; 44, 15–23. Crossref

53. Villarejo LG, Gerding WM, Bachmann L, et al. Optical genome mapping reveals genomic alterations upon gene editing in hiPSCs: implications for neural tissue differentiation and brain organoid research. Cells 2024; 13, 507. Crossref

54. Pinkel D, Segraves R, Sudar D, et al. High-resolution analysis of DNA copy number variation using comparative genomic hybridization to microarrays. Nat. Genet. 1998; 20, 207–211. Crossref

55. Hamley JC, Li H, Denny N, Downes D, Davies JOJ. Determining chromatin architecture with Micro Capture-C. Nat. Protoc. 2023; 18, 1687–1711. Crossref

56. Lieberman-Aiden E, van Berkum NL, Williams L, et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 2009; 326, 289–293. Crossref

57. Fang H, Eacker SM, Wu Y, et al. Genetic and functional characterization of inherited complex chromosomal rearrangements in a family with multisystem anomalies. Genet. Med. Open 2025; 3, 103423. Crossref

58. Yoon JG, Lee S, Cho J, et al. Diagnostic uplift through the implementation of short tandem repeat analysis using exome sequencing. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2024; 32, 584–587. Crossref

Affiliations

Philip Hublitz, Vipul Patel, Felix Hermann, Manuel Landesfeind, and Matthias Austen, Evotec International GmbH, Göttingen, Germany

Heloise Philippon, Evotec SAS, Lyon, France

Lukas Gebauer and Alexander Vogt, Evotec SE, Hamburg, Germany

Authors for correspondence: philip.hublitz@evotec.com and matthias.austen@evotec.com

Authorship & Conflict of Interest

Contributions: The named authors take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Andrea Cossu, Tanja Schneider, Andreas Scheel, and Dominik ter Meer for critical reading and insightful suggestions on the manuscript.

Disclosure and potential conflicts of interest: The authors are Evotec employees. Philip Hublitz is a ByoRNA invited board member, and holds a patent: EP25195521.7. Vipul Patel, Lukas Gebauer, Manuel Landesfeind, and Matthias Austen are Evotec SE stockholders. Felix Hermann is a Cimeio Therapeutics AG stockholder. Matthias Austen is an inventor on several pending patent applications related to pluripotent stem cells, their expansion and/or differentiation.

Funding declaration: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Article & Copyright Information

Copyright: Published by Cell & Gene Therapy Insights under Creative Commons License Deed CC BY NC ND 4.0 which allows anyone to copy, distribute, and transmit the article provided it is properly attributed in the manner specified below. No commercial use without permission.

Attribution: Copyright © 2025 Philip Hublitz, Vipul Patel, Heloise Philippon, Lukas Gebauer, Alexander Vogt, Felix Hermann, Manuel Landesfeind, and Matthias Austen. Published by Cell & Gene Therapy Insights under Creative Commons License Deed CC BY NC ND 4.0.

Article source: Externally peer reviewed.

Submitted for peer review: Sep 15, 2025.

Revised manuscript received: Nov 13, 2025.

Publication date: Nov 26, 2025.